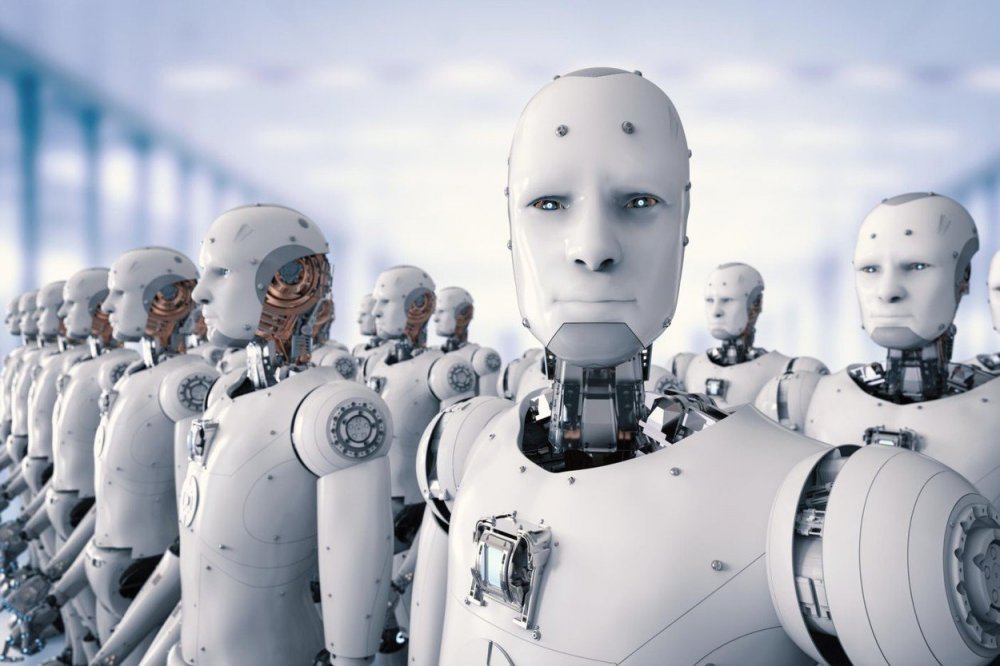

Demonization: The machine wants to kill us (well, according to pop culture)

One of the favorite narratives in pop culture (games, novels, comics and films) is tech dystopias. It’s actually rare to find a true utopia depicted in the science-fiction genre. If we survey only films and how humans interact with everyday machines, we’ll find a killer elevator (The Lift, 1983), a killer fridge (The Refrigerator, 1991) and a killer car (Christine, 1983). If we expand our search to include “evil” robots, the list is longer: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Westworld (1973), The Terminator (1984), Runaway (1984), Chopping Mall (1986), Robocop (1987), Hardware (1990), Death Machine (1994), Evolver (1995), Screamers (1995), The Matrix Reloaded (2003) and I, Robot (2004).

The same narrative appears even in music. In the song “Yoshimi Battles The Pink Robots,” you’ll hear: “Those evil-natured robots, they’re programmed to destroy us.” Pink Floyd’s “Welcome to the Machine” includes a disturbing line: “What did you dream? It’s alright we told you what to dream.”

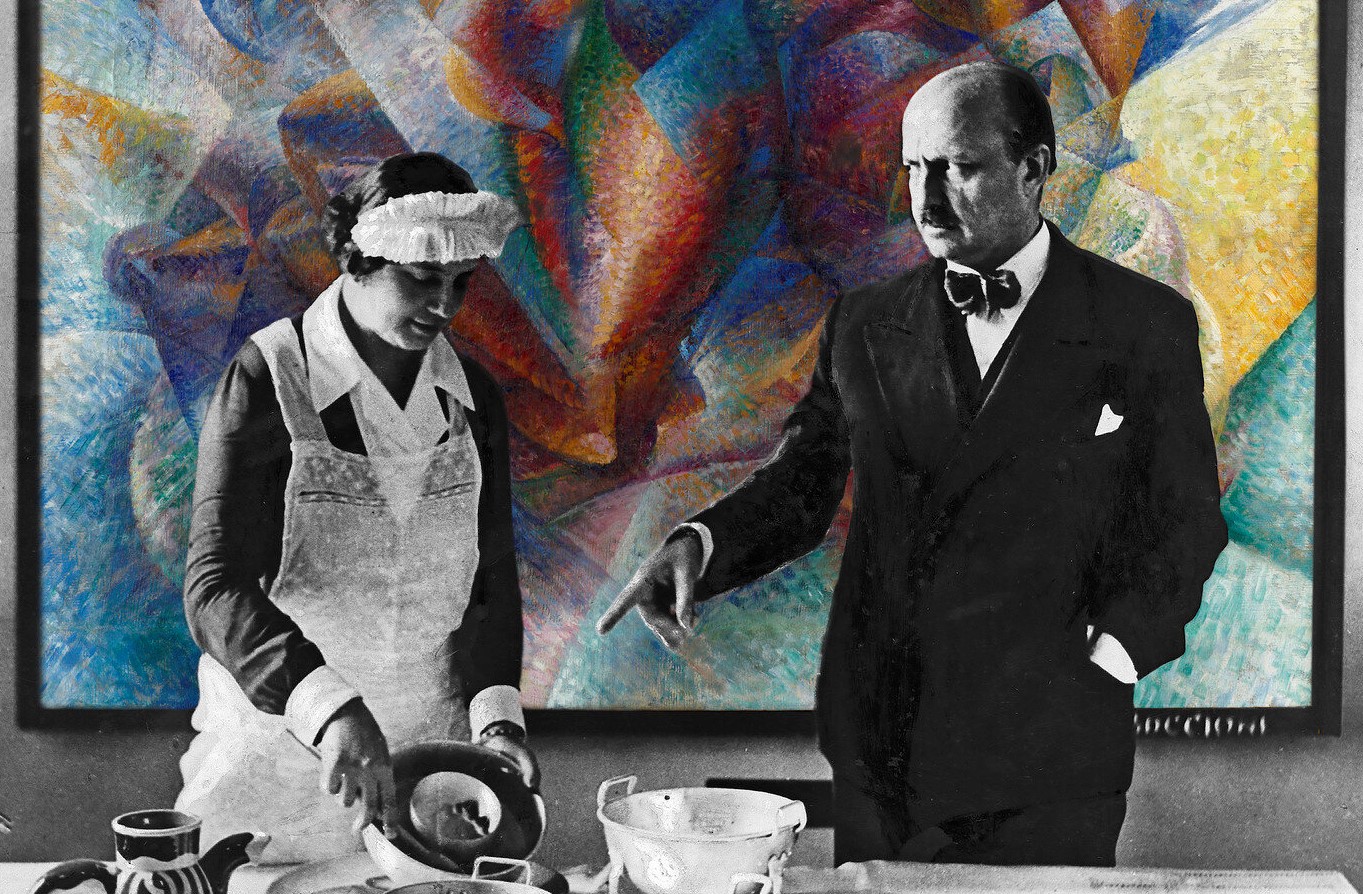

It was not always such a grim future living with machines. There was always the luddites of 19th century, then the techno-pessimism post-WWI. However, it was the Nazi “industrialized” extermination centers and the nuclear attacks on Japan of WWII that relegated that dream to a footnote in the history of ideas. Techno-utopianism had its heyday in the late 19th century and into the early decades of the 1900s. Many scientists, thinkers and writers subscribed to the idea that technology could certainly improve our world. That optimism about a technological future resulted in a literary and artistic movement called Futurism, made up mostly of Italian members. Its founder Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) made statements of extreme glorification towards industrialization.

Scouring through Marinetti’s eccentric writings from a century ago, we’ll find that he talked about “the machine” in three different manners: one that deified it, another that humanized it, and on occasion, he hoped for a future of a man-machine merger. All such three types of relationships with machines still resonate with us to different extents.

Deification: The machine as god

Examine the following statements from Marinetti:

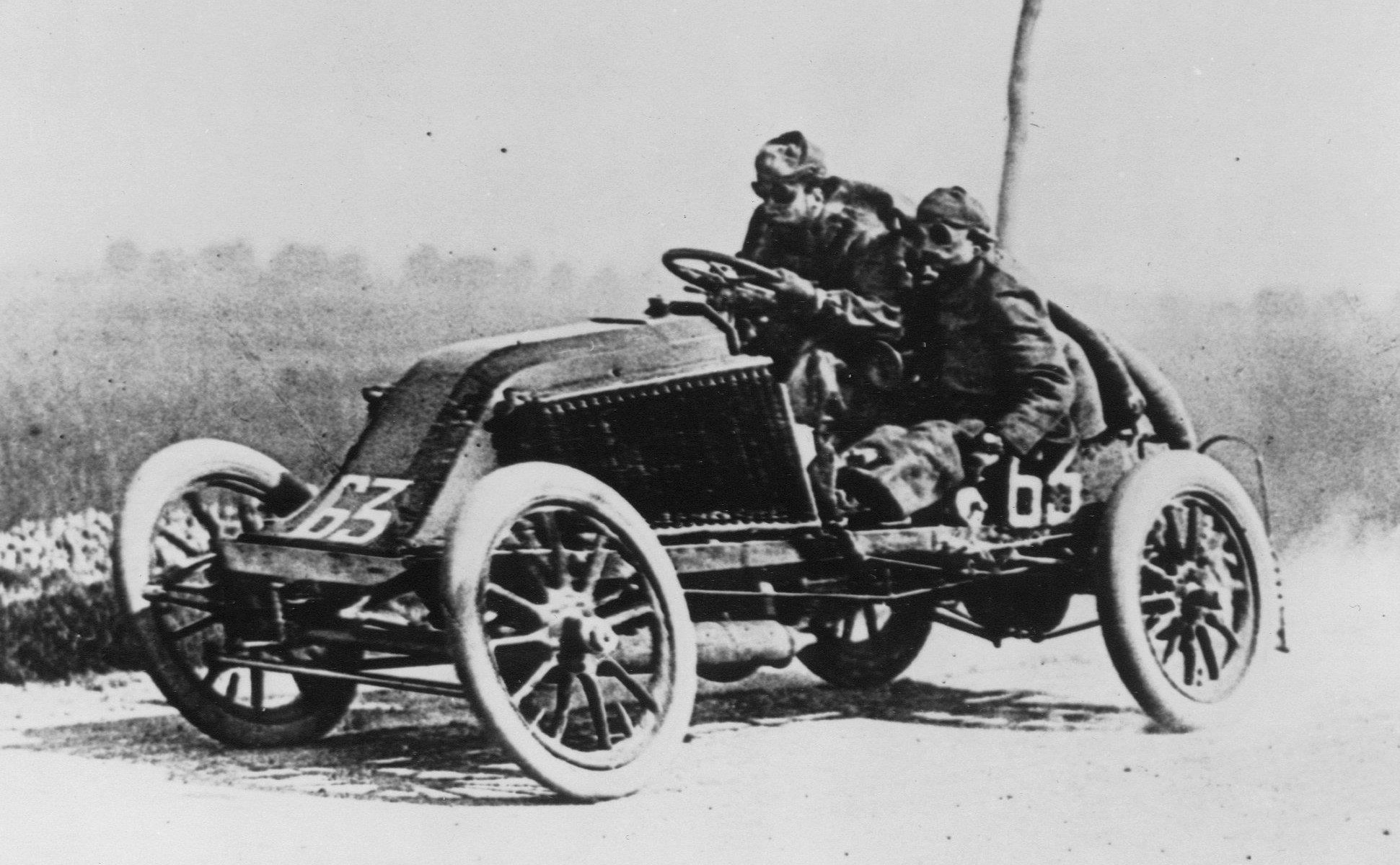

If praying means communicating with the divine, then hurtling along at great speed is a prayer. The sanctity of wheel and rail track. Kneel on the track to pray for divine speed! One must kneel before the spinning gyrocompass.1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 255.

Combustion engines and rubber tires are divine. Bicycles and motorcycles are divine. Gasoline is divine. So is religious ecstasy inspired by one hundred horsepower. And the joy of moving from third to fourth gear. The joy of pressing down on the accelerator. The growling pedal of musical speed. Disgusting the people entangled in sleep. The feeling of revulsion I experience when going to bed at night. I pray every night to my little electric lamp, for it has formidable speed at work within it. 2Ibid., 256.

Clearly, when Marinetti wrote “kneel before the gyrocompass” or “I pray every night to my little electric lamp,” he didn’t mean he believed they were self-conscious deities. The question that remains, however, is why he used such exaggerated language.

There is a prophetic undertone in the words of Marinetti. Over centuries of innovations, we progressed from easy-to-understand simple tools, to mechanical tools, to electro-mechanical tools, to today’s highly complex, electronic equipment. We feel alienated from the metaphorical “machine” embodied in the tools we use everyday without real understanding about their inner workings. But we have no doubt about the power of “the machine.”

The machine is super intelligent. It has knowledge beyond our comprehension. The machine could take your job away or give you a new job. It could ruin your life. It could ruin your finances. It could make you rich or dry up your savings. The machine knows more about you than you do about yourself. The machine might even decide in the coming decades who to live and who to die. The machine is everywhere. Heck, it seems that the machine is omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent. The machine is god!

Could the future turn Marinetti’s “machine-worship” metaphor into a reality? Probably. It is predicted that AI will be an inspiration for new religions. In fact it’s already happening. In 2017, a former Google executive Anthony Levandowski started Way of the Future, the first Artificial Intelligence church. The official website claims it’s “a church for those who want to create a peaceful and respectful relationship with Artificial Intelligence.”

Humanization: The machine as one of us

This is the most common type of relationship we have with machines, whether they’re appliances, vehicles, computers, robots or AI. We give names to our cars, boats and even coffee machines. We develop feelings for robots and anime characters. We give human conversational skills to AI like Siri, Alexa, Cortana and Hal. We give robots, like the famous Sophia, humanoid facial features to mimic our expressions. We yell insults at our computers in frustration as if they’re listening and capable of changing their behavior.

Many popular movies reflect that affinity where robots are humanoid, conscious and act out of free will. In Ex Machina (2015), Caleb falls in love with the robot Ada. In the movie Her (2013), Theodore falls in love with Samantha, an AI virtual assistant through her voice. WALL-E (2008) is a robot that longs for love and expresses emotions like humans.

Now being aware of how machines are portrayed in mass media, the erotic language Marinetti used a hundred years ago suddenly seem less bizarre:

[W]e are promoting the love of the machine—that love we first saw lighting up the faces of engine drivers, scorched and filthy with coal dust though they were. Have you ever watched an engine driver lovingly washing the great powerful body of his engine? He uses the same little acts of tenderness and close familiarity as the lover when caressing his beloved. […] his great, faithful, devoted friend, whose heart was ever giving and courageous, his beautiful engine of steel that had so often glistened sensuously beneath the lubricating caress of his hand? 3Ibid., 85.

(It should be noted that Marinetti showed more affection in his articles towards machines than he did towards women!)

Marinetti penned these words seven whole decades before Stephen King published a novel, in 1983, featuring the “jealous” and “overly-sensitive” car, Christine:

You will undoubtedly have heard the comments that car owners and car workshop managers habitually make: “Motorcars, they say, are truly mysterious… They have their foibles, they do unexpected things; they seem to have personalities, souls and wills of their own. You have to stroke them, treat them respectfully, never mishandle them nor overtire them. If you follow this advice, this machine made of cast iron and steel, this motor constructed according to precise calculations, will give you not only its due, but double and triple, considerably more and a whole lot better than the calculations of its creator, its father, ever dreamed of!”

Well then, I see in these words a great, important revelation, promising the not-too-distant discovery of the laws of a true sensitivity in machines! 4Ibid., 86.

He similarly humanized (feminized) machine guns:

“Ah yes! you, little machine gun, are a fascinating woman, and sinister, and divine, at the driving wheel of an invisible hundred horsepower, roaring and exploding with impatience.” (Inventing Futurism)

Even though we are well aware that machines are just made of steel, circuits and algorithms, why do we desire to humanize them? Why one out of four people name their car? Why Davy Crockett, the legendary frontiersman, named one of his rifles “Old Betsy” and the huge German gun of WWII was nicknamed “Big Bertha”?

We have a tendency to anthropomorphize inanimate objects, that is attributing human characteristics and emotions to them. The main character, played by Tom Hanks, of Cast Away (2000) named a ball Wilson. Hurricanes get names too. But there’s more to the human-machine interaction than this natural tendency.

There is a need to feel safe and comfortable around machines. We want to reduce the gap between us and them. As tools and gadgets continue to invade our personal spaces, we want to feel in control. We want to see them as servants to us. Anthropomorphizing our machines could also be related to our innate fears that they might replace us at work, or turn against us. But despite a hundred years of incredible advancement in technology since the Futurists “promoted the love of the machine,” they are still far from experiencing the world objectively or feeling emotions.

Hybridization: The machine merging with us

One of the ideas that fascinated Marinetti was the machine-extended, humano-mechanical new man. Later in the century, this idea would become a movement, called transhumanism. The adherents of that movement believe that we should aspire to enhance our bodies using advances in artificial intelligence, biology, nanotechnology and cognitive science. Marinetti’s article on post-humans titled “Extended Man and the Kingdom of the Machine” (1910) was so ahead of its time, it preceded by 13 years the first and sensational book on the subject of transhumanism: Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1923) by J. B. S. Haldane.

We believe in the possibility of an incalculable number of human transformations, and we are not joking when we declare that in human flesh wings lie dormant. 5Ibid.

The new race of “non-human, mechanical species” he envisioned will not concede to the limitations of humans today:

The extended man we dream of will never experience the tragedy of old age! 6Ibid., 88.

Marinetti’s fantasy is still alive among those studying the possibility of immortality through cryonics, mind uploading and genetic modification to defy the biological degradation of ageing.

The idea of a man who defies mortality, a superhuman, the Übermensch could be found in ancient myths. Only in the 20th century, it became clear that at least some of its ideas could become reality. For now, humans, or cyborgs, equipped with memory implants, infrared eyesight and mind-controlled bionic prostheses is still the stuff of science fiction.

Sometimes the question arises of whether philosophy today is dead. There are those who claim that all questions have been asked, and answers have already been offered. The truth is philosophy is alive and well and it will be preoccupied, perhaps sooner than we expect, with a question that Marinetti himself never had to consider: How do we define “human” when we’re increasingly becoming hybrids with machines?

You might also like:

Futurism: On turning speed into a pseudo-religious experience

‘Speed is Divine’: Why the Italian poet Marinetti spoke of speed in religious terms

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Futurists vs Romantics: Extreme views on technology and nature

Gazing at the stars, from Goethe, Marinetti to Google Sky

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes