The Sorrows of Young Werther is an epistolary novel—that is, a collection of letters. The writer is the tragic character Werther and the recipient is his friend Wilhelm. Werther is a wealthy young man who moved to the rural town, Wahlheim, to do some painting and enjoy the countryside. From the beginning, there were ominous signs that the hero is too emotional:

I treat my little heart like a sick child: whatever it wishes for is granted. Don’t spread this about; there are people who would hold it against me. 1Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther, trans. Burton Pike (New York: Random House, 2004), 10.

Werther realizes that he follows his heart, rather than his head—his feelings, rather than clear and rational thinking.

The author, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, was a significant figure in early years of the Romantic movement which originated in Germany. Romanticism, despite the name, was not only concerned with love-related matters, but with emotions and sentimentality. The young men and women who endorsed this mindset were reacting against the Enlightenment and its preachers of rational thinking. They struggled to come to terms with industrialization that was about to take over their world. Modern descendants of the Romantics poised against destructive industrialization could be seen in those fighting to protect the environment. However, for a parody of the modern Romantic, watch Brendan Fraiser in his movie Bedazzled, weeping over the sight of the sunset.

He meets a girl, Charlotte (Lotte), at a dance, with whom he immediately falls in love. She’s struck by him for being of similar passionate character like her and for reading the same literature. Early on, he expresses his feelings towards her in extreme words, which foretell his destiny:

Wilhelm, to be honest, I swore an oath to myself that a girl that I loved, and on whom I had a claim, should never waltz with anyone but me, even if it cost me my life! 2Ibid., 27.

However, she’s engaged to be married, and she, while infatuated with Werther, remains faithful to her fiancé. Lotte believes, she could keep Werther as a friend while being Albert’s wife. Even though Werther knows he can never have her, he continues to visit her and develop an obsession about her:

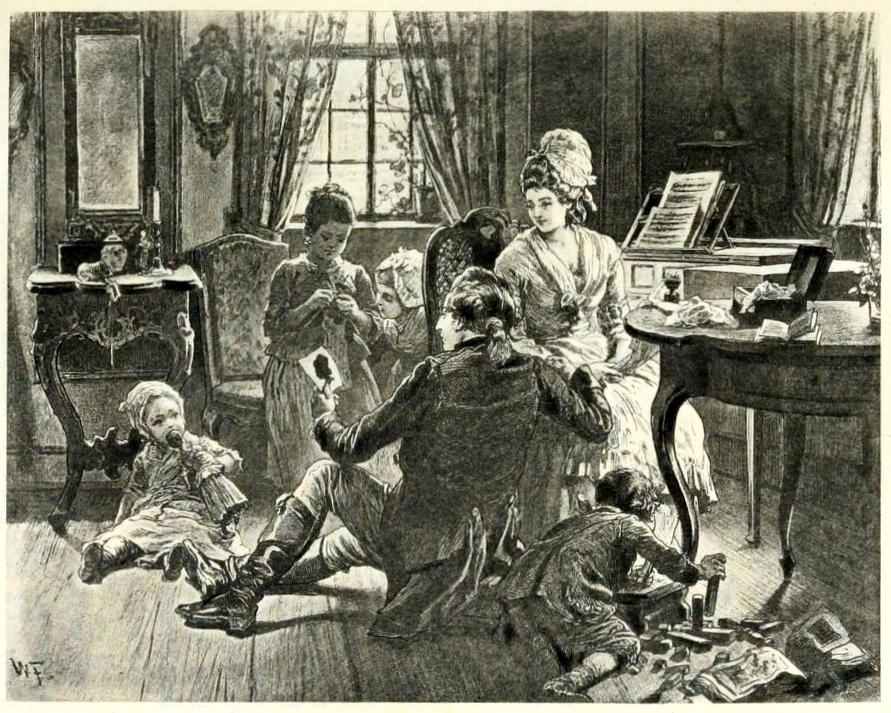

She is sacred to me. All desire falls silent in her presence. I never know what is happening to me when I am with her; it’s as if my nerves are turning my soul inside out.—She has a melody that she plays on the clavier with the power of an angel, so simply and so spiritedly! It is her favorite song, and as soon as she strikes the first note it stills all my pain, confusion, and fancies. Not a word about the old magic power of music is improbable to me. How the simple song seizes me! And how she knows when to play it, often at a time when I would like to put a bullet through my head! It disperses the darkness and confusion of my soul, and I breathe more freely again. 3Ibid., 43.

I sent my servant there, just to have a person around me who will have been near her today. How impatiently I awaited him, with what joy I saw him again! I would have gladly clasped his head and kissed him if I wouldn’t have been ashamed. We are told about the Bononian stone that, if you place it in the sun, draws the sun’s rays and shines for a while at night. That’s how it was with the fellow. The feeling that her eyes had rested on his face, his cheeks, on the buttons of his jacket and the collar of his coat, made these things so sacred, so dear! I wouldn’t have parted with the lad at that moment for a thousand talers. I felt so happy in his presence.—God forbid this should make you laugh. Wilhelm, are those phantoms, when we are happy? 4Ibid., 44.

He mocks his mother’s advice who knows that her rich son having no occupation could be a hazard to himself:

You say that my mother would be happy to see me engaged in some activity: that made me laugh. 5Ibid., 45.

He tries to free himself from thoughts of his beloved taking over his mind by returning to one of the original reasons he moved to this town, to paint:

[M]y power to represent is so weak, everything swims and totters so before my soul, that I cannot get hold of an outline. 6Ibid.

Meanwhile Werther sees in Albert, the fiancé of Charlotte, a great contrast to himself. First of all, he’s got a job! He could support a family, and he’s also down-to-earth and reliable.

I don’t know whether I have written you that Albert is to stay here and receive from the court, where he is highly regarded, a position with a decent income. I have rarely seen his like for order and industrious-ness in business matters. 7Ibid., 50.

After Werther meets Albert and realizes that he stands no chance in competing with him, the suicide solution becomes nearer than ever to his mind. He even debates with Albert the morality of suicide. While Werther agrees with Albert that it’s morally wrong, he presents analogies to explain that there are exceptions. He compares it to someone who steals to feed his one’s family. Someone who kills to avenge infidelity. A married girl who has extramarital sex with a person she loves. These acts are treated differently by the law, he says. Extreme passion moves these people and the same with those who kill themselves, hence they should be looked upon with sympathy:

Yet, my dear fellow, I went on, here too you find a few exceptions. It is true that stealing is a vice: but the person who sets out to rob to save his family from imminent starvation, does he deserve pity or punishment? Who raises the first stone against the married man who in righteous anger sacrifices his unfaithful wife and her despicable seducer? Against the girl who in a blissful hour loses herself in the inexorable joys of love? Our laws themselves, these coldblooded pedants, let themselves be moved and suspend their punishment.

That is quite different, Albert replied, because a person whose passion carries him away loses all his powers of thought and is regarded as drunk, as insane. 8Ibid., 52

Albert does not agree that a suicidal person is overtaken by passion as in the examples Werther provided.

Werther got angry towards Albert.

O you reasonable people! I cried, smiling. Passion! Drunkenness! Madness! You stand there so calmly, so uninvolved, you moral people! You scold the drinker, loathe the weak-minded, pass by like the priest and thank God like the Pharisees [Jewish sect condemned by Jesus as hypocrites] that He has not made you as one of these. I have been drunk more than once, my passions were never far from madness, and I don’t regret either: for despite my limitations I have learned to understand how all exceptional people who created something great, something that seemed impossible, have from time immemorial been vilified as drunks and madmen. But it’s unbearable in everyday life too to hear shouted after almost every halfway free, noble, unexpected deed: the person is drunk, he’s an idiot! Shame on you sobersides! Shame on you wise men! 9Ibid., 53.

Albert reasserts his view that committing suicide is weak and cowardly, and those who do it are not in the grip of passion.

Those are more of your fancies, Albert said. You exaggerate everything and are certainly wrong at least here, in comparing suicide, which is what we are talking about, with great deeds [the crimes of passion above], since one cannot regard it as anything but a weakness. For of course it is easier to die than steadfastly to bear a life of agony. 10Ibid.

Human nature, I went on, has its limits. It can bear joy, sorrow, pain up to a certain point, but buckles as soon as that point is passed. So the question here is not whether one is weak or strong but whether he can endure the extent of his suffering. It may be moral or physical: and I find it just as strange to say that the person who takes his life is cowardly as it would be out of place to call someone a coward who dies of a malignant fever. 11Ibid.

Then Werther recounted to Albert a story of a young woman who drowned herself after her rejection by her lover. The story shows how Werther esteems suicide in certain cases as romantic and quasi-heroic:

[S]he finally comes across a man to whom an unknown feeling draws her irresistibly, on whom she casts all her hopes, forgets the world around her, hears nothing, sees nothing, feels nothing but him, the only one, longs only for him, the only one. Not spoiled by the empty pleasures of inconstant vanity, her desire draws her straight to the goal, she wishes to become his wife, she wants to find in an eternal bond all the happiness she is lacking, enjoy the union of all the joys she longs for. Repeated promises that seal the certainty of all her hopes, bold caresses that increase her desires, take complete hold of her soul; she hovers in a hazy awareness, is eager to the highest degree in a foretaste of every joy. Finally she stretches out her arms to embrace all her desires—and her beloved deserts her.—Numb, senseless, she stands before an abyss; everything is darkness around her, no prospect, no comfort, nowhere to turn! For he has abandoned her, he in whom alone she had felt all her being. She doesn’t see the wide world lying before her, the many others who could replace her loss, she feels alone, abandoned by everyone—and blindly, driven to desperation by the horrible need in her heart, she jumps off in order to suffocate all her torments in an enveloping, embracing death.

[…]Woe to him who could look on and say: The fool! If she had waited, if she had let time do its work, her despair would surely have subsided, another man would have turned up to comfort her.—That’s just like saying: The fool, dying of fever! If he had waited until his strength returned, his circulation improved, the tumult of his blood calmed down, everything would have turned out well and he would still be alive today! 12Ibid., 55.

It might strike modern readers as odd that Werther uses, of all tragic cases, the fever victim as someone whose life is likely to be cut short. Unlike today, those who suffered from severe fevers during the 18th and 19th centuries rarely survived. It was almost always mysterious since the underlying causes were never understood. Hence, in Werther’s view, the suicidal person could be compared to someone with fever: both are in unbearable pain, they could not be blamed for the circumstances and can not change them, death is inevitable and would be a merciful conclusion to their suffering, be it physical or emotional.

Albert implies that he still does not accept any reason to give up on life, even if one is terminally ill. Their conversation goes nowhere. In some sense, they inhabit different worlds:

[W]e parted without having understood one another. As in this world no one easily understands another. 13Ibid.

Werther continues to feel stuck in a hopeless love triangle which takes a toll on him. He writes:

Must it be, that what makes for man’s happiness becomes the source of his misery? The full, warm feeling of my heart toward living nature, that flowed over me with such bliss, that made the world around me a paradise, has now become an unbearable torturer, a tormenting spirit, that pursues me wherever I turn. 14Ibid., 57.

(Note in the above quote, Werther, like his generation of Romantics, sought peace and a safe refuge from the odious urban life in Nature.)

The reader realizes Werther’s is taking a turn for the worse, when he writes that he cries himself to sleep:

[I]n vain I seek her at night in my bed, deceived by a happy, innocent dream, as if I were sitting beside her in a meadow holding her hand and covering it with a thousand kisses. Alas, when still half in the toils of sleep I feel cheered and reach out for her— a stream of tears breaks forth from my oppressed heart, and I weep inconsolably toward a dark future. 15Ibid., 59.

His words become more alarming:

I can’t do anything, either. I have no powers of imagination, no feeling for nature, and books nauseate me. When we have lost ourselves, we have lost everything. I swear to you, sometimes I wish I were a day laborer, just to have when I wake up in the morning a prospect of the day to come, an obligation, a hope. 16Ibid., 60.

He shockingly declares to his friend:

Adieu! I see no end to this misery but the grave. 17Ibid., 62.

Wilhelm had been offering Werther to help connect him with a job, but Werther was not very interested. Later, Werther admits his jealousy of Albert’s success and starts considering taking the job. Perhaps it could serve as a break and a distraction from his emotional torment:

I often envy Albert, whom I see buried up to his ears in files, and imagine myself happy in his place! More than once I have awakened with a start, I was on the point of writing you and the Minister to petition for the position at the embassy that, as you assure me, would not be denied. I think so myself. The Minister has liked me for a long time, and has long been after me to devote myself to some kind of business; and for a while I’m really tempted. 18Ibid.

He takes a job with an ambassador, the job recommended by his friend. However, his relationship quickly sours with his employer. Unfortunately, we’re not surprised to see Werther blaming his friend for finding him a job, playing the typical role of a victim, rather than taking any responsibility:

And it is all your fault, all you who have nattered me into the yoke and preached to me so much about being active. Being active! 19Ibid., 74.

He could see that he won’t last long at his job. Particularly that he is too sensitive to take in the soft criticism by his boss.

I am afraid that my ambassador and I are not going to be together much longer. […] He complained about me recently at Court, and the Minister gave me a rebuke that may have been gentle but was still a rebuke.20Ibid., 79.

After getting mocked at a social party behind his back, he felt snubbed by the entire aristocratic milieu. He became furious and wanted to commit murder but then immediately brought the murderous fantasy against himself:

I wanted one person to dare reproach me so I could drive a dagger through his body; if I could see blood I would feel better. Oh, I have grabbed a knife a hundred times to ease this oppressed heart! They tell of a noble race of horses that, when they are terribly driven and overheated, instinctively bite open a vein to help themselves breathe. I often feel that way, I would like to open one of my veins, to bring me eternal freedom. 21Ibid., 83.

Finally he decides to walk away and resign from his job:

I have requested my dismissal from Court […] tell my mother gently; I cannot help myself, and she will just have to accept that I can’t help her either. Of course she will be hurt. To see the fine career that her son was just beginning, leading to privy councillor and ambassador, suddenly brought to a halt.22Ibid., 84.

Then he requested from his friend to ask his mother to send him money.

He stays with a local nobleman with the title, Prince, who’s interested in Werther’s knowledge and cultural background. He’s open to sharing the fruits of his fine education:

What I know anyone can know—my heart is mine alone. 23Ibid., 87

In the above quote, Werther summarizes the Romantic ideal which is his knowledge could be shared anyone, but only he, himself, knows what’s in his heart, how his heart feels—its torment and its agony.

Werther continues to fight dark and bloody thoughts:

When I lose myself in dreams this way I cannot help thinking: What if Albert were to die? You would! Yes, she would—and then I chase after the will-o’-the-wisp until it leads me to abysses before which I draw back trembling. 24Ibid., 90

In another letter, Werther tells his friend of recent events regarding a servant (“a peasant lad”), who was helplessly in love with his employer, a widow with no intention of remarrying. Werther sees himself in the story of that servant whose love was rejected:

He was not able to eat or drink or sleep, his throat constricted, he did what he ought not to have done, what he was ordered to do he forgot; he was as if pursued by an evil spirit, until one day, when he knew she was in an upstairs room, he went after her, or rather he was drawn to go to her; since she paid no attention to his pleadings he tried to overcome her by force, he didn’t know what was happening to him, God was his witness that his intentions toward her had always been honorable, and that he wished for nothing more devoutly than that she should marry him, that she would spend her life with him. 25Ibid., 92

To our shock, we find Werther, the sensitive and cultured man, sympathizing with the servant after his attempted rape on the widow. By now, Werther had fantasized about the death of Albert and condoned forceful sex, the reader wonders what could happen next.

The servant was punished by being ejected by the whole community and was replaced. Not only he could no longer see her, he also lost his job.

Werther descends further into melancholy:

I have so much, and my feeling for her swallows up everything. I have so much, but without her everything becomes nothing. 26Ibid., 100.

God knows, I often lie down to sleep with the desire, even sometimes the hope, not to wake up again; and in the morning I open my eyes, see the sun again. 27Ibid.

His friend suggests finding solace in God. Werther responds by comparing himself to Jesus Christ himself on the cross who cried out in a famous quote why God had forsaken him. Clearly, he’s deluded by making this comparison. Yet another sign revealing that he finds a heroic aspect to his mental anguish.

I honor religion, you know that, I feel it is a staff for many weary souls, refreshment for many a one who is pining away. But—can it, must it, be the same thing for everyone? If you look at the great world, you see thousands for whom it wasn’t, thousands for whom it will not be the same, preached or unpreached, and must it then be the same for me? Does not the son of God Himself say that those would be around Him whom the Father had given Him? But if I am not given? If the Father wants to keep me for Himself, as my heart tells me?—I beg you, do not misinterpret this, do not see mockery in these innocent words. 28Ibid., 102.

The servant mentioned earlier, finds out that his employer whom he loved will marry his replacement. He becomes mad and he kills the new servant. Werther rushes to the scene. After the servant’s arrest, Werther steps up to defend him. But his defense is not persuasive and Werther is even more dispirited that he failed to save the servant:

I am in a state which those wretches must have been in of whom one believed that they were being tossed about by an evil spirit. 29Ibid., 119

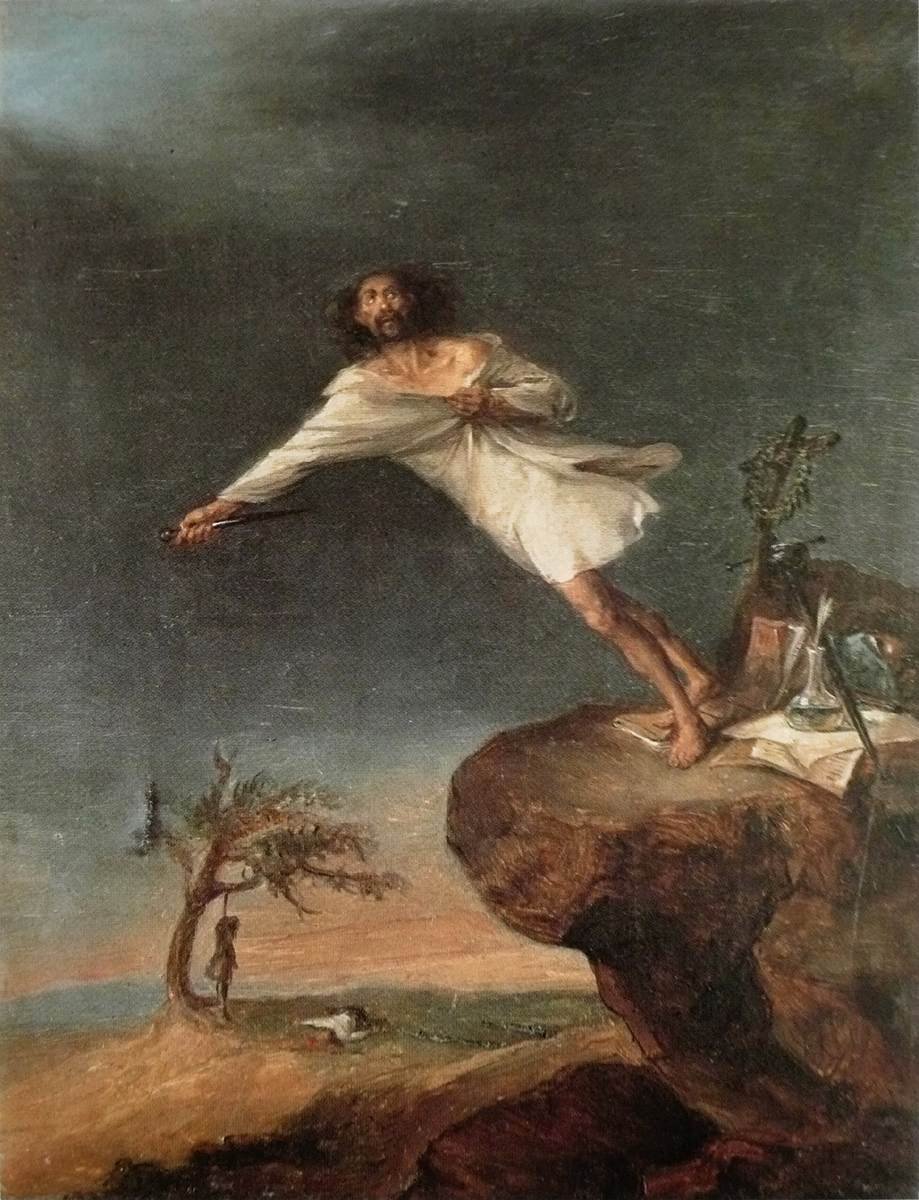

While Wahlheim is being battered by a storm, Werther watches the floodwaters from a cliff and fantasizes about jumping off:

Oh, I stood above the abyss with outstretched arms and breathed: down! down! 30Ibid., 120.

Lotte! Lotte!—And I am finished! My mind is all confused, for a week I have had no power of consciousness, my eyes are filled with tears. I am happy nowhere and happy everywhere. I wish nothing, desire nothing. It would be better for me if I went away. 31Ibid., 121.

Albert had told Lotte that, to put an end to the town gossip, Werther needs to be seen less with her. Lotte addresses the problem directly by talking to Werther:

Why me, Werther, why precisely me, the property of another?

…

And should there not be in the whole wide world a girl who could fulfill your heart’s desire? Get hold of yourself, go look for her, and I swear to you, you shall find her; for I have long been disturbed, for you and for us, by the isolation you have shut yourself up in while you have been here. Get hold of yourself! A trip will distract you, must distract you! Seek, find, an object worthy of your love, and come back and let us enjoy the blessedness of a true friendship together! 32Ibid., 124.

She tells him that he should stop his frequent visits. Werther is not really paying attention to her words. He believes she’s being pressured by Albert.

The following day, Werther sat down to write his suicide note in advance:

It is decided, Lotte, I want to die, and I write you this without romantic exaggeration, calmly, on the morning of the day on which I shall see you for the last time. When you read this, my dearest, the cool grave will cover the stiff remains of the restless unfortunate, who knows no greater sweetness in the final moments of his life than to converse with you. I have had a horrible night, but oh! one that did me good. The night strengthened my resolve, determined it: I want to die! As I tore myself away from you yesterday, my senses in a fearful uproar, how it all rushed to my heart, and my hopeless, joyless existence at your side seized me with horrible coldness— I barely reached my room, I threw myself on my knees, beside myself, and, dear God, You granted me the ultimate relief of the bitterest tears! A thousand violent shocks, a thousand prospects raged through my soul, and finally it was there, firm, whole, this one final thought: I want to die!—I lay down, and in the morning, in the calm of waking, it is still firm, still quite strong in my heart: I want to die!—It is not despair, it is certainty that I have settled on, and that I am sacrificing myself for you. Yes, Lotte! Why should I keep silent? One of us three must go, and I want it to be me! 33Ibid., 125.

In an uncharacteristic behavior, Werther acts responsibly and settles his debts and other matters in anticipation of what’s to come.

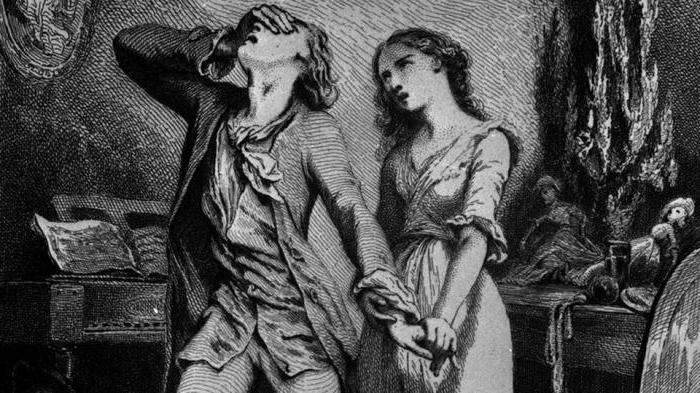

Then he goes to visit Lotte one final time. Albert is away on business. She reproaches him for not listening and dropping in for a visit so soon. Nevertheless, she’s happy to see him. She feels awkward to be alone with him, in absence of Albert, so she suggests reading epic poems. He reads on loudly and they’re both moved to tears by the power of the tragic poetry. He throws the book aside and grabs her in his arms.

Frantic with despair, he threw himself down before Lotte, seized her hands, pressed them to his eyes, against his forehead, and an intimation of his terrible purpose seemed to fly through her soul. Her senses became confused, she pressed his hands, pressed them against her breast, bent down to him with a melancholy gesture, and their burning cheeks touched. The world was blotted out for them. He threw his arms around her, pressed her to his breast, and covered her trembling, stammering lips with raging kisses.—Werther! She called out in a suffocated voice, turning away, Werther!—and with a weak hand pushed his breast from hers.—Werther! she cried in the composed tone of the noblest feeling.—He did not resist, released her from his arms, and threw himself down senseless before her. She tore herself away, and in fearful confusion, trembling between love and anger, she said: This is the last time! Werther! You shall not see me again.—And with a glance full of love at the poor unfortunate, she hastened into the adjoining room, locking the door behind her. Werther stretched out his arms after her, did not dare hold her back. He lay on the floor, his head on the sofa, and remained in this position for more than half an hour, until a noise brought him to his senses. It was the maid, who wanted to set the table. He paced up and down the room, and when he found himself alone again went to the door of the adjoining room and called out in a soft voice: Lotte! Lotte! Just one more word! A farewell!—She was silent. He waited and begged and waited; then he tore himself away and cried: Farewell, Lotte! Farewell forever! 34Ibid., 137.

Werther went home and wrote a note for Albert requesting his hunting pistols claiming he’s going on a journey. He sent his servant with the note.

[Werther’s boy servant] handed the note to Albert, who turned calmly to his wife and said: Give him the pistols.— I wish him a pleasant journey, he said to the boy. —That struck like a lightning bolt, she tottered to her feet, she did not know what was happening to her. Slowly she went over to the wall, trembling took down the pistols, wiped them off, hesitated, and would have delayed still longer if Albert had not compelled her by a questioning look. She handed the unhappy instruments to the boy without being able to utter a word, and when he was out of the house she picked up her work and went to her room in a state of the most inexpressible uncertainty. Her heart prophesied all sorts of horrors. Soon she was on the point of casting herself at her husband’s feet, revealing everything to him, the story of the previous evening, her guilt and her presentiments. Then again she saw no way out of such an undertaking, least of all could she hope to talk her husband into going to Werther. […] The boy came to Werther with the pistols, he took them with delight when he heard that Lotte had handed them to him. He had bread and wine brought, told the boy to go eat, and sat down to write. They have passed through your hands, you have wiped the dust from them, I kiss them a thousand times, you have touched them. 35Ibid., 143-144.

He recorded his final thoughts in his last letter:

Albert, I have repaid you badly, and you will forgive me. I have disturbed the peace of your house, I have brought mistrust between you. Farewell! I want to end it. Oh, that my death might make you both happy! Albert! Albert! Make the angel happy! And thus may God’s blessing dwell over you!

…

All is so quiet around me, and so calm my soul. I thank You, God, for giving me this warmth, this energy in these final moments.36Ibid., 144.

At midnight, with a steady and determined hand, he shot himself in the head. The shot doesn’t immediately kill him, he dies the following morning. When the news reaches Lotte, she drops to the floor unconscious. She’s unable to attend the funeral and suffers severe depression. Albert doesn’t attend the funeral either, keeping by her side out of concern that she might attempt to harm herself as a result of the news. Since suicide is forbidden by the Church, no priests attends the funeral either. Thus, his departure from the world is as sad and lonely as was his life.

You might also like:

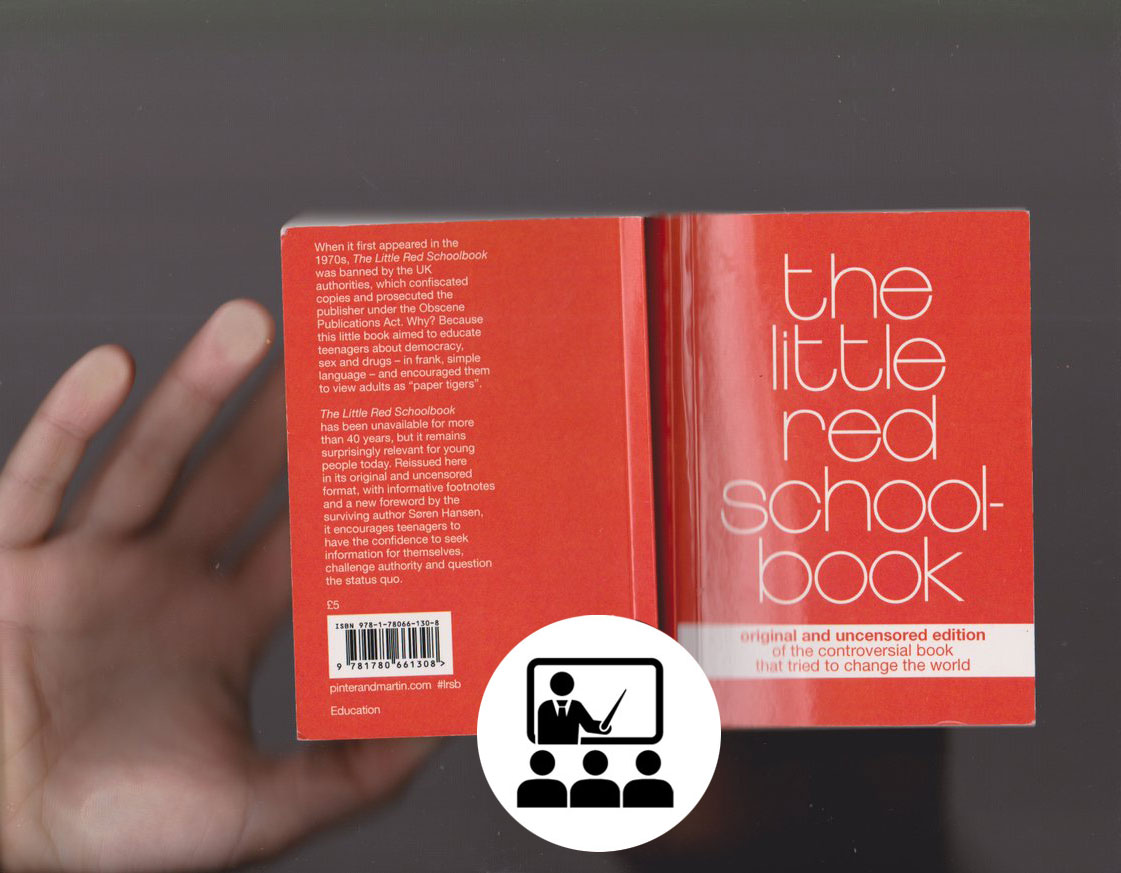

The Little Red Schoolbook: The challenging bits on education

Controversial advice from the schoolchildren’s book on education

BOOK: THE LITTLE RED SCHOOLBOOK

The Giver: The passages about euthanasia and suicide

Why the dystopian novel was considered inappropriate for its young audience? Read the passages on euthanasia and suicide

BOOK: THE GIVER

Endnotes