“The New Ethical Religion of Speed”

The above was the title of an article written by Italian poet Filippo T. Marineti in 1916. He was also the founder of Futurism, an artistic and social movement (1908-1944) that aimed to celebrate modernity and all its products. Marinetti explained his ideas in several articles, some of which contained bizarre and grandiose statements. Here is an excerpt from his article:

In my first manifesto of February 20, 1909, I declared that the splendor of the world had been enriched by a new beauty, the beauty of speed. […]

Christian morality served the purpose of developing man’s inner life, but today it no longer has any purpose, since the Divine is utterly finished.

Christian morality protected man’s physical self from the excesses of sensuality. It regulated his instincts and gave them a certain balance. Futurist morality will protect man from decrepitude brought on by lethargy, nostalgia, fastidiousness, immobility, and custom. Human engines, increased a hundredfold by speed, will command Time and Space.1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 253.

Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto: “Time and space died yesterday”

When he wrote the words above, he had been preaching the benefits of life in the fast lane for many years. In his Futurist Manifesto which was published in 1909 on the front page of Le Figaro he wrote:

We want to sing about the love of danger, about the use of energy and recklessness as common, daily practice.2Ibid., 13.

We wish to sing the praises of the man behind the steering wheel, whose sleek shaft traverses the Earth, which itself is hurtling at breakneck speed along the racetrack of its orbit. 3Ibid.

He declared in his manifesto that speed had become omnipresent in modern life:

Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the realms of the Absolute, for we have already created infinite, omnipresent speed.4Ibid., 14.

Marinetti: Sleep is for losers, gasoline is divine

Elsewhere he spoke of a “religious ecstasy,” he finds in dangerous, petrol-powered activities:

Combustion engines and rubber tires are divine. Bicycles and motorcycles are divine. Gasoline is divine. So is religious ecstasy inspired by one hundred horsepower. And the joy of moving from third to fourth gear. The joy of pressing down on the accelerator. The growling pedal of musical speed. Disgusting the people entangled in sleep. The feeling of revulsion I experience when going to bed at night. I pray every night to my little electric lamp, for it has formidable speed at work within it.5Ibid., 256.

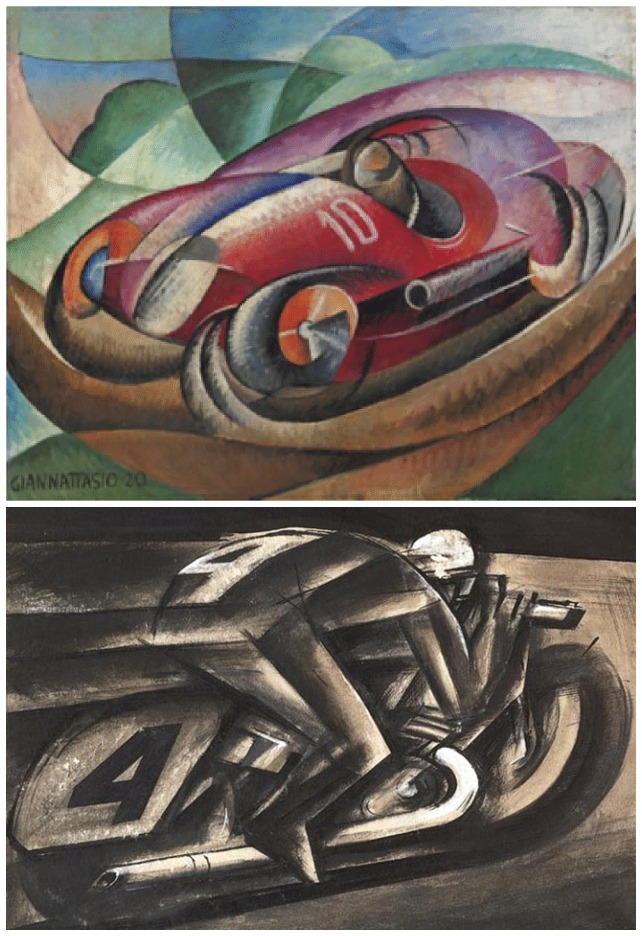

The Futurist movement left its strongest mark on art. A major theme of Futurist art was the depiction of automobiles, trains and motorcycles.

High speed religion: When was Marinetti’s Damascene moment?

If speed is some kind of religion for Marinetti, then there must be a moment of conversion, akin to St. Paul’s conversion to Christianity while on the road to Damascus. That moment would be the motorcar accident that nearly killed the Italian poet in 1908:

When I got myself up—soaked, filthy, foul-smelling rag that I was—from beneath my overturned car, I had a wonderful sense of my heart being pierced by the red-hot sword of joy.6Ibid., 13.

He wrote of automobile racers as the first members of this “religion”:

The exhilaration of high speeds in a motor car is simply the joy of feeling oneself made one with the one divinity. Sportsmen are the first neophytes of this religion. Before long comes the destruction of houses and cities to create huge meeting places for cars and airplanes.7Ibid., 255.

Some in the public thought that the master of stunts and grand statements was speaking metaphorically about a new religion. He was not. In fact, he had a vision of replacing Catholicism with his “new” mystical religion:

In order that we may arrive at the Futurist precepts of the ephemeral, of speed, and of continuous, heroic struggle, we must burn the priests’ black robes—symbols of inertia—and melt down all the church bells to turn them into wheels for new superfast trains.8Ibid., 325.

What explains such veneration of speed by the founder of Futurism?

Before the 19th century, the fastest speed a human could attain was on top of a horse. By the end of the century, steam locomotives was nearing the dizzying milestone of 100 mph (161 km/h). For thousands of years, humans relied on wheels and animals for speed. Now a huge, noisy and terrifying machine cutting through villages could reach a speed never seen before. Automobiles, which were becoming popular, were even faster. By 1904, they reached the same milestone. Those who lived in the city watched in awe fast-moving passengers, goods, news and communication. The main thing that the Futurists could see in common between the telegraph, telephones, cars, trains and airplanes is speed. They’re all inventions that sped up life.

One could only speculate why Marinetti found these experiences religious in nature. Perhaps it was simply an exaggerated reaction by a group of young men discovering a pleasurable experience that was never available to their ancestors. It’s hard to imagine this movement being launched by a group of women. Scientic evidence has been documented proving that “fast cars boost men’s testosterone levels” which also explains why men are more likely to speed than women.

Another possible explanation is that there is a human tendency to worship what we fear. That could be fire (Zoroastrians), a volcano (Hawaiian mythology), a fierce animal (tigers in Vietnamese folk religion), a flooding river (the Nile for the Egyptians) or just a deity capable of protecting us as in all monotheistic religions. What intimidated humans at the beginning of the 19th century was, not the forces of nature, but that new force of speed capable of crushing them in tragic accidents. It actually often did. However Marinetti admired it and fully endorsed it. He went further. He spoke of speed in poetic veneration that was often exclusive to religion.

At the beginning of the century, young men’s fascination with speed appeared in Futurist paintings, as shown above, for the first time, close to the end of the century, it evolved into other media like music and movies. Examples in music could be found in the sub-genres of power metal and speed metal. Below is an example:

The Czech-born French author Milan Kundera wrote in 1995 about this modern fascination:

Speed is the form of ecstasy the technical revolution has bestowed on man. As opposed to a motorcyclist, the runner is always present in his body, forever required to think about his blisters, his exhaustion; when he runs he feels his weight, his age, more conscious than ever of himself and of his time of life. This all changes when man delegates the faculty of speed to a machine: from then on, his own body is outside the process, and he gives over to a speed that is noncorporeal, nonmaterial, pure speed, speed itself, ecstasy speed.

Comedian Bill Maher remarked about driving-themed movies on his show: “What does it say about our psyche that Hollywood can always count on men to plunk down 10 bucks to watch another man make a motor go vroom vroom!”

For the pioneer of the Futurist movement, speed was much more than “fast cars.” It was a way of life. He preached it as a solution to his struggling nation to join the industrial age:

Only speed can kill off the noxious, nostalgic, sentimental, pacifist, and neutralist Moonlight. Italians, be speedy, and you will be strong, optimistic, invincible, immortal.9Ibid., 259.

He spoke of speed as a new kind of virtue that we should all aspire to attain:

After the destruction of the age-old good and the age-old evil, we are creating a new good, which is speed, and a new evil, which is torpor.

Speed = the synthesis of every kind of courage in action. It is aggressive and warlike.

Torpor = the analysis of every sort of festering caution. It is passive and pacifist.

Speed = scorn for all obstacles, desire for the new and the unexplored. It represents modernity and moral health.

Torpor = stasis, enchantment, immobile admiration of obstacles, nostalgia for things already seen, idealization of weariness and inactivity, distrust of the unexplored. Rancid, romantic concepts of the wild, wandering poet; of the filthy, shock-headed, bespectacled philosopher.10Ibid., 255.

Today we are no less obsessed with speed than the Italian Futurists were a century ago

Our pursuit of a faster tempo of life did not abate over the last 100 years. In fact, it increased in strange ways. We eat fast food, have quickie sex, take power naps and request fast-acting drugs. We buy books that claim to teach us Japanese in 10 days and C++ programming language in 24 hours. We buy groceries that is pre-washed, pre-cooked, pre-peeled and pre-sliced. We even buy entire meals that are pre-prepared. We often multi-task. In living rooms, we divide our attention between the TV and the smartphone. We opt for faster shopping, faster payment and faster deliveries. We seek faster computers and data plans with faster downloads. We continue to explore new methods for speed dating, speed reading and speed listening. We manipulate speeds of videos and podcasts to consume their content faster. How much faster is fast enough? How much faster is healthy and sustainable?

You might also like:

Italian Futurists: The first to love and worship the machine

The machine demonized, deified, humanized and eventually merged with us

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Futurists vs Romantics: Extreme views on technology and nature

Gazing at the stars, from Goethe, Marinetti to Google Sky

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes