The Futurists’ utopian attitude to technology

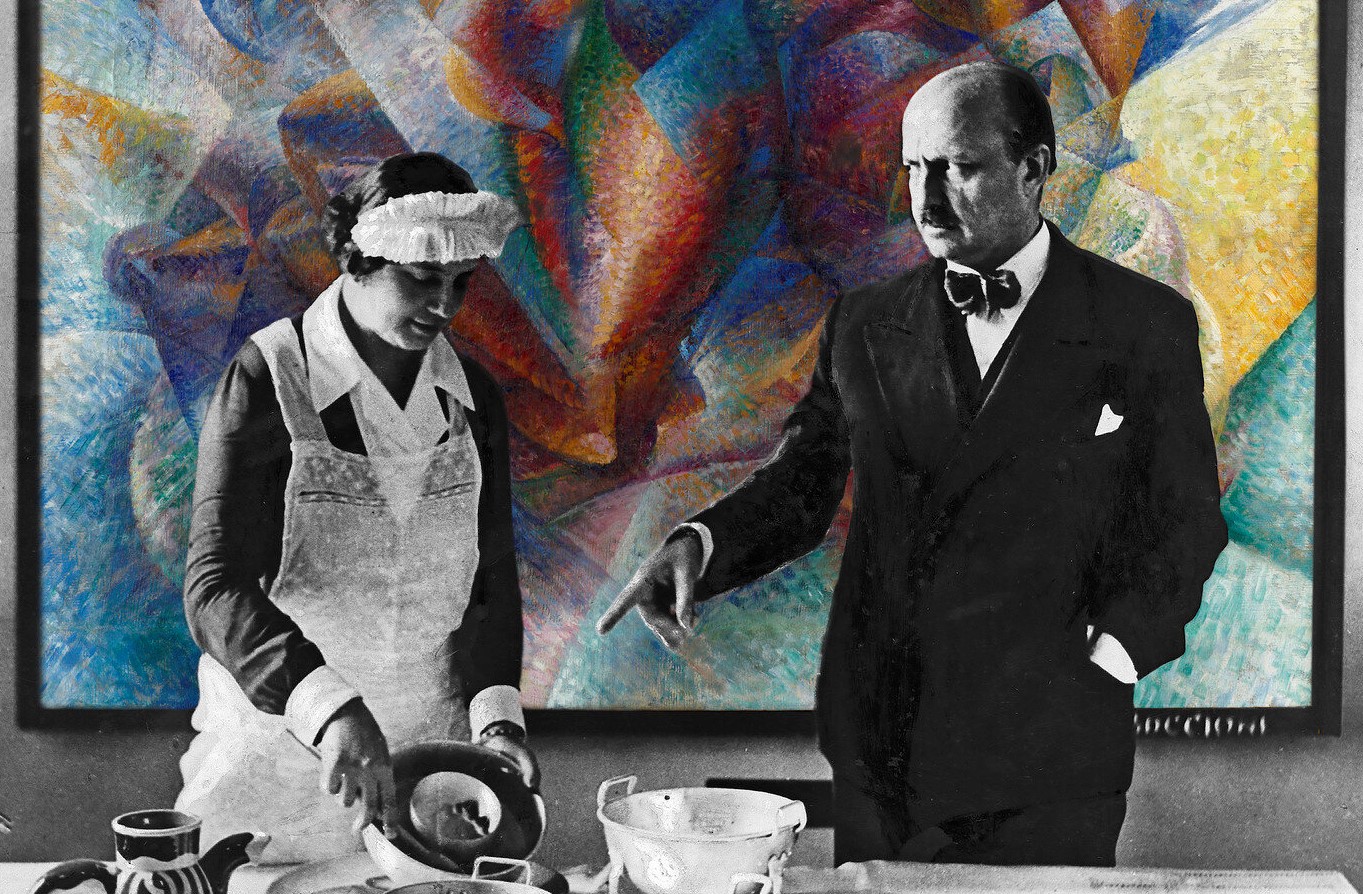

Ground-breaking inventions often trigger a wide range of reactions. Italian poet, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founded Futurism at the beginning of the 20th century which was on the extreme end of optimism towards technology. Futurists, like him, believed that humans are about to arrive at new consciousness. Here is how he described the Futurist movement in 1916:

Futurism is based on the complete renewal of human sensibility brought about by the great discoveries made by science.1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 120.

To the Futurist, nature was a force to be emulated, controlled and dominated:

We must steal from the stars the secret of their stupendous, incredible speed. Let us take part in the great celestial battles and face the star bolts, hurled by invisible cannons. 2Ibid., 255.

Marinetti was perhaps the first in history to celebrate modern technology with such praise. For generations before him, the fast-industrializing Europe was viewed in the milieu of artists, with cynicism, and even hostility. One such group was historically called the Romantics.

The Romantic cynicism towards technology

Romantic artists and philosophers, around the 19th century, were wary of industrial development and urbanization. Their attitude was exemplified by how they viewed the recently invented-optical instruments, like telescopes and microscopes. They denounced them as tools that would separate us from nature. Their belief was that while they enable us to see more, they deprive us of a more natural sensory experience, as they intervene between us and the physical objects. They also argued that such instruments focus only on tiny segments while magnifying the insignificant. At worst, the context could be lost leading to a distorted understanding of the cosmos. Among the most prominent philosophers who decried the use of optical instruments was the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), best known for his tragic play Faust. He preferred the human eye:

“Microscopes and telescopes really only serve to confuse the unaided human senses.”

The Futurist founder: Let us kill the moonlight!

The Romantics, like their bohemian and hippie descendants, emphasized the importance of being in touch with nature. When the Futurists arrived on the art scene, they brutally mocked them and called them fools. Slogans by Marinetti like “let us kill the moonlight!” were aimed specifically at them. Nature, in the eyes of the Futurists, was inferior:

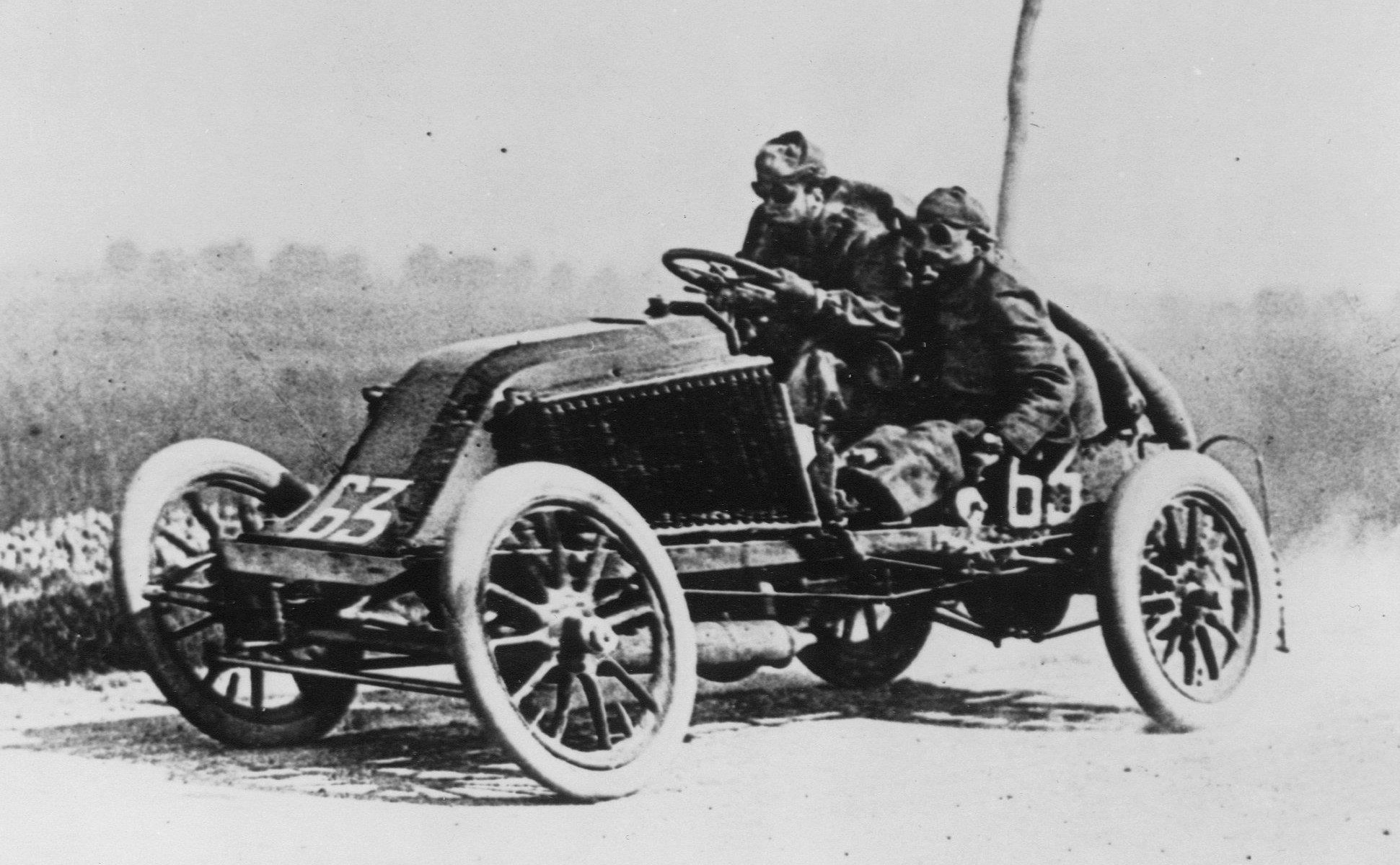

[O]ur Futurist sensibility is no longer moved by the dark mystery of an unexplored valley or of a mountain gorge which, against our wills, we imagine. Instead, they are traversed by an elegant ribbon of white road where, all of a sudden, coughing and spluttering, an automobile comes to a halt, gleaming with progress and full of civilized voices—like the corner of a boulevard set down in the middle of nowhere.

Every pine wood madly in love with the moonlight has a Futurist road crossing it from one side to the other.

[…]Multicolored billboards in the green meadows, iron bridges which chain the hills together, surgical trains that cut through the blue belly of the mountains, huge turbines, new muscles of the earth, may you be praised by the Futurist poets, since it is you who are destroying the old morbid sensibilities and the billing and cooing of the earth! 3Ibid., 44-45.

The telescope was just the beginning

With each new motorway, machine, gadget or widget, another barrier was raised between humans and the natural world. In hindsight Goethe’s warnings were valid and are still relevant today. Ironically, philosophers like Goethe were mistaken to assume that humans would try to refrain from being detached from the natural world. Ordinary experience of the natural world, i.e. reality, seems insufficient for our needs. We now use technology to enhance the physical environment (“augmented reality“), for example, by overlaying information on our smartphone screens as we view an object through a phone’s camera. Also, we create “virtual reality” environments and soon we might even have experiences of “hyperreality,” where we can’t tell the difference anymore between fact and fantasy.

Then there is also virtual reality, the 3D immersive environments for purposes such as flight training, battlefield training, surgery practice, and gaming. This type of simulation can take you on a virtual field trip to another country or even a different century, where you can enact events outside the boundaries of real time. Virtual reality is not limited to 3D environments. In some sense, the Internet as a whole, with its online communities and social networks is yet another form of virtual reality. It annihilates space and time limitations for information access and telecommunications. It allows people to work and play any time, and from any place. 3D printers promise a future where we can re-imagine matter and customize it to our own personal whims. As such, the three elements that make up the fabric of reality (read: the natural world), space, time and matter are now breaking up in cyberspace. A Harvard Business Review blogger described that pursuit as follows:

“[T]he most obvious opportunities involve shifting from the reality of time, space, and matter to the virtuality of no-time, no-space, and no-matter, including playing computer games, exploring virtual worlds, probing real-world simulations, connecting via social media, or even just surfing the World Wide Web.”

To observe the skies, we no longer need the telescope. Actually, we don’t even need the sky. Instead, we turn to cyberspace and software tools like Microsoft’s WorldWide Telescope and Google Sky. There we can view a simulation of the sky, real-time satellite imagery or even historical maps of the sky. We can revisit how the sky looked like when the Apollo 11 moon landing happened or what the sky will look like next Thursday night when we go stargazing. Goethe, who once decried telescopes and microscopes, most probably would have rejected innovations such as cyberspace and Google Sky for the same reasons.

Looking back, it seems like technological innovation went the way of the Futurists. Without the telescope, one of the most important inventions of the Scientific Revolution, we wouldn’t have reached the moon or sent exploration rovers to Mars. Technology solved and continue to solve major questions that have been facing humanity for millennia. However, a major question remains: How future generations will handle their shift further away from the natural world and into the digital one?

You might also like:

Italian Futurists: The first to love and worship the machine

The machine demonized, deified, humanized and eventually merged with us

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Futurism: On turning speed into a pseudo-religious experience

‘Speed is Divine’: Why the Italian poet Marinetti spoke of speed in religious terms

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes