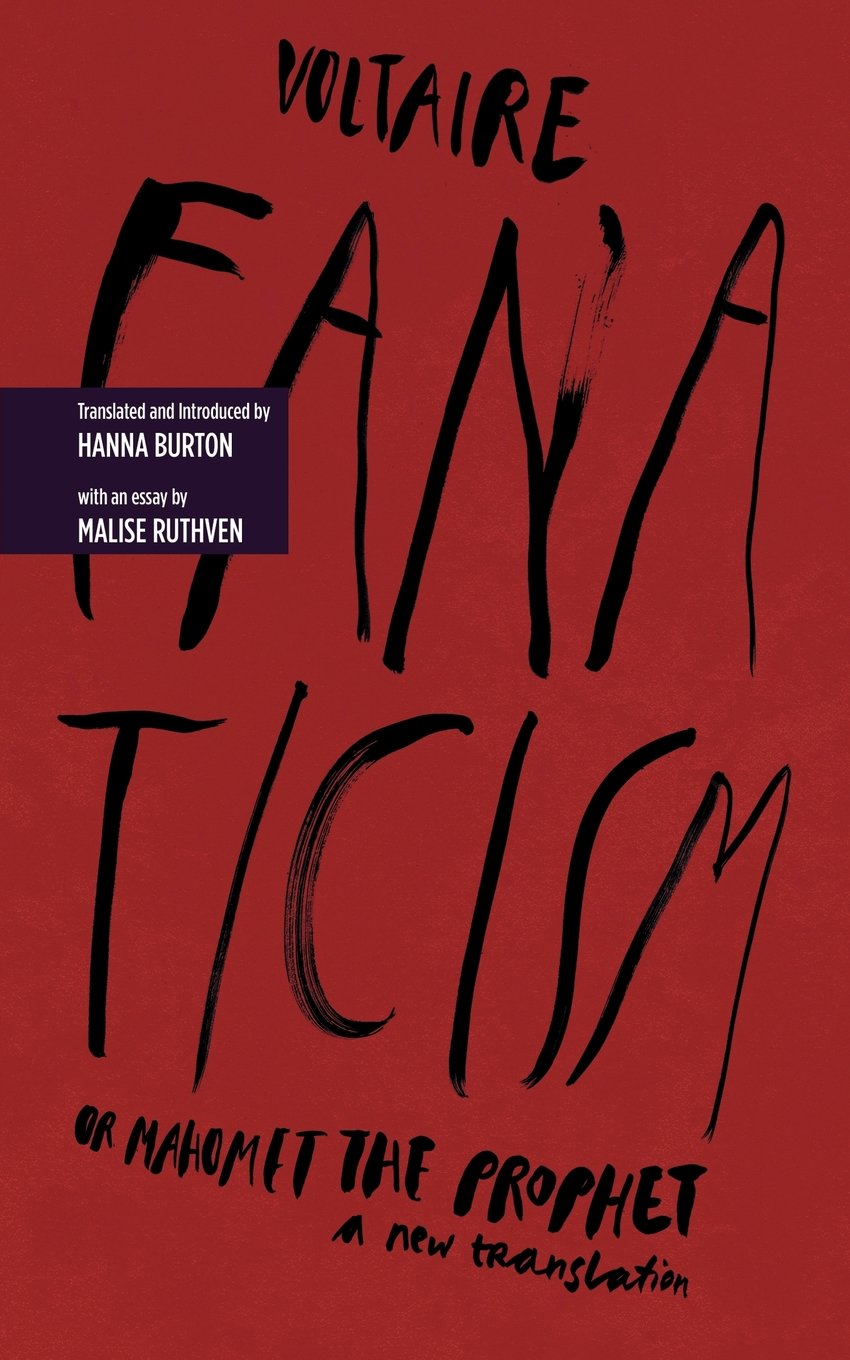

Note: Almost all of the events of Voltaire’s play are fictional although it was inspired by an actual story, the conquest of Mecca, from the life of Muhammad.

We learnt at the beginning of the play that Mahomet (spelled as written in Voltaire’s play), the founder of Islam, was exiled from his native city, Mecca. He’s already a successful conqueror but Mecca is not yet under his rule. He sets up a siege of the city whose army leader, Zopir, remains a polytheistic believer of Arabia’s ancient gods and rejects Mahomet and his divine “revelation.” There’s a truce between the enemies and they’re supposed to discuss the terms of peace. Right from the start, Zopir is presented as a defendant of freedom while the Prophet of Islam is presented as an impostor. Zopir recalls that Mahomet killed his wife and two children many years ago, but he also killed Mahomet’s son.

Zopir argues with the senator of Mecca, Phanor, against a peace deal:

ZOPIR: Who, me? Just look the other way as this fanatic performs his so-called miracles? And bow down before his charades? Honor him here in Mecca and after having banished him? No! If I should compromise my integrity by encouraging revolt and commending deceit, may the righteous gods punish me.1Voltaire, Fanaticism, or Mahomet The Prophet, trans. Hanna Burton (Sacramento: Litwin Books, 2013), 39.

Phanor agrees but he acknowledges that a peace deal is necessary to avert war, especially that some in their midst in Mecca have already adopted Islam:

PHANOR: When he was one of our citizens you saw Mahomet as an obscure upstart, a despicable rebel. But now he’s a prince and enjoys glory and power. He’s an impostor in Mecca, while in Medina he’s a prophet. He has thirty nations extolling the very crimes we deplore here. Meanwhile, within our own city is a group of misguided souls all too eager to guzzle the poison of lies and perpetuate the illusion of his false miracles. They spread fanaticism and sedition, and they’re calling in his army. They believe a fearsome God has granted him inspiration, guidance, and invincibility. 2Ibid.

But Zopir believes that a peace deal is in vain:

ZOPIR: With that traitor? You cowards! It would bring nothing but salvery. Go ahead, then! Fall to your knees to serve and glorify this idol that will crush you all with his weight. 3Ibid., 40

Later, we find out that the two children of Zopir who he believes were killed are still alive. Palmira and Seid have been living with Mahomet since he kidnapped them in their infancy fifteen years earlier. They’re loyal to him since he cared for them as “orphans.” Even after Mahomet was banished out of Mecca, they’re still devoted to him. Zopir is not aware that Palmira and Seid are his own children.

Omar, the right arm of Mahomet, arrives with the terms of the peace deal, offering a portion of the spoils. Zopir rejects Mahomet’s offer:

ZOPIR: Forget the charades and turn a wise eye on this prophet you revere. See Mahomet for the man he is and how much you exalt your beloved apparition. Stop with all this cheating and religious fervor; use your powers of reason and join me in judging your master. You’ll see a lowly camel-driver who flagrantly wronged his first wife and who tempts the faith of worthless scum for the sake of an outrageous dream. 4Ibid., 46

Omar tries to tempt him with further political power:

OMAR: The people are blind and weak and were born to admire and believe great men and follow our commands. If you fear servitude, come and reign with us. Share in our greatness instead of detracting from it. Don’t imitate the mobs; make them cover. 5Ibid., 47

Zopir declares he will not submit to Mahomet:

ZOPIR: Do you think they’ll listen to me as I defend my laws, gods, and country? Or to your impious rebuttals in the name of a persecuting god, the terror of the human race? A god proclaimed by a fraud with weapons held high?

(To Phanor) Phanor, help me drive this traitor out. To tolerate his presence among us and spare him is its own form of betrayal. Let’s thwart his plans and crush his pride. Retribution or death! With support from the Senate I can save my country and the world from this tyrant. 6Ibid., 49

In a final attempt, Mahomet goes to face Zopir and threaten him to submit to his forces:

ZOPIR: I’m ashamed only for you, whose artifice has dragged your country to the brink, whose hands have planted the seeds of crime here and cultivated war in peaceful lands.

Here your name alone has the power to divide families: wives, husbands, mothers, daughters, fathers, and sons. For you a truce is a new way to twist the blade. Everywhere civil unrest follows you, the appalling figure of lies and nerve, the tyrant of your people. So you come to offer peace and proclaim your god? 7Ibid., 57

MAHOMET: I rule Medina and make Medina tremble. If you fear your demise, accept my peace. 8Ibid., 59

MAHOMET: The sword and the Qur’an in my bloodstained hands brings silence down on everyone else. My voice is thunder to them, and they kneel to touch their foreheads to the earth. But now the man in me speaks candidly; great as I am, there’s no need to deceive you. Find out more about who I am. We’re alone, so listen: I’m ambitious, just as all men are, but no king, chief, pontiff, or citizen ever conceived of a project as great as mine. All people enjoy brilliance in their turn: through the arts, through law, and, most of all, through war. Arabia’s time has come at last. These noble people, unknown for so long, have kept their glories buried in the sand, but these new days are marked for victory. From north to south the world is in distress. Persia is drenched in blood, its empire felled. India has become a timid slave, and Egypt’s dignity has been debased. Constantine’s splendid walls are eclipsed, and Rome is falling apart limb by limb, its severed members drained of all honor and life. Let us raise Arabia upon the debris. The blind world is in need of new laws, a new religion and a new god. Osiris in Egypt, Zoroaster in Asia, Minor in Crete, and Numa in Italy, easily dispensed inadequate laws to people with no morals, creeds, or kings. I have come a thousand years later to change the crude laws of states with a new, nobler yoke, abolishing false gods. My purified faith is the cornerstone of my ever-expanding grandeur. Don’t for one minute blame me for betraying my homeland as I destroy idols and weakness. I’ll reunite its people with one god and one king. It won’t know glory until it’s enslaved. 9Ibid., 57-58

Zopir completely rejects his offer and accuses him of being barbaric:

ZOPIR: So these are your intentions! You have the nerve to think you can mold the world to your whims and order people to think like you do, even as you bring them nothing but carnage and fear? You ravage the world while claiming to educate it? Ah! If we get drawn in by your fallacies and stray into the night of error, what dreadful torn will you bring to enlighten us? By what right do you predict and instruct, claiming empires and god’s authority? 10Ibid., 58

After the doomed encounter ends, Mahomet talks to Omar and demands the murder of Zopir:

MAHOMET: I need someone who will do what I say, who will commit the murder and pass the rewards to me. 11Ibid., 62

Earlier we learn that Mahomet, who’s got several wives and concubines, had set his eyes on Palmira. But he noticed that there’s a growing affection between her and Seid who don’t know they’re siblings. He reveals his jealousy to Omar:

MAHOMET: I secretly prefer Palmira to my wives, so can you imagine my jealous rage when she fell before me and confessed a fatal love that’s sheer effrontery? That gave me a rival? 12Ibid., 56

Omar tells him that Seid is the perfect candidate for that murderous mission. Seid who had been indoctrinated in extremism and utter obedience to Mahomet would take on the killing of the infidel Zopir as a religious duty. A young passionate man like him is ideal for manipulation:

OMAR: Youth is blinded by fanaticism and love, his weakness will stoke his rage. 13Ibid., 70

Mahomet immediately likes the plan which would free the way for him to have Palmira to himself.

Seid tells Palmira of his plan to kill Zopir but she objects that this deed goes against nature, the merciful values of religion and love. In way of enticing her to accept his mission, Seid tells her that the Prophet is ready to bless their union if he takes this hazardous mission.

Mahomet encounters Palmira and reminds her to be obedient and and supportive of Seid’s religious duty if she wants his blessing to their love. Palmira changes her mind and gives in.

In the following scene, Seid expresses to Mahomet hesitation about the mission. Mahomet assures him that his mission is approved by God:

MAHOMET: There is no honor apart from following his commands. Blind executor of His divine decrees: adore and strike! You will be armed by the angel of death and the God of hosts. 14Ibid., 71

Mahomet orders him to just obey:

MAHOMET: Whoever dares to think was not born to believe me. Obeying me in silence is your only glory. (Ibid.)

At the end, both religious conviction and the desire to have Palmira drive Seid to look forward to committing the murder.

SEID: I believe I hear the voice of God. Speak, and I will obey.

MAHOMET: Obey and strike. Stained with the blood of an impious man, you will earn eternal life by his death. 15Ibid., 72

Later when he’s alone, Seid’s heart still questions the mission:

SEID: Sacrifice a poor defenseless old man who has taken me hostage? It doesn’t matter! A victim brought to the altar falls there helplessly, and his blood will please Heaven. After all, God has chosen me to make this great sacrifice. I vowed to do it so I must. Help me, you will have felled the tyrants of the world. Add your rage to my intrepid zeal; guide this hand to its holy murder. Angel of Mahomet, exterminating angel, instill the depths of my heart with your ferocity! 16Ibid., 70

Seid is in the presence of Zopir who is wondering why the young man seems disturbed, then expresses his bewilderment at his extremist convictions:

ZOPIR: Fascinated by the laws of a tyrant you think that everything, apart from being a Muslim, is a crime. Desperately submissive to your master’s teachings you loathed me before you even met me. A frightening prejudice has ensnared your innocent heart in an iron trap. I forgive you the errors to which Mahomet has led you, but can you believe in a god that commands hatred? 17Ibid., 73

At this encounter, Seid fails to complete the mission.

An Arab reveals the long-held secret in a letter to Zopir that Seid and Palmira are his own children. Mahomet and Omar find out that the identity of the pair’s father has been revealed and that Seid did not carry out the act.

Palmira goes to see Seid who is struggling with the purpose of Mahomet’s plot.

SEID: Enlighten my spirit and guide my hand. Act in the place of a god I do not understand. Why did He choose me? Can the commands this terrifying prophet interprets be revoked? 18Ibid., 79

PALMIRA: We should tremble at the thought of questioning. Mahomet sees our hearts, hears our sighs, and observes our tears. Everyone fears the divinity in him. This is all I know: doubt is blasphemy, and his victories prove that the god he proclaims so proudly is true. (Ibid.)

Seid responds:

SEID: I can’t fathom why a benevolent god who is the father of humankind has chosen me to commit an appalling murder. I know too well that my doubt is a crime, that a priest slits the throat of his victim without remorse, that the voice from Heaven has condemned Zopir, and that I was predestined to uphold my creed. Mahomet explained himself and I had to remain silent. Proud to serve His wrath, I go to bring death to the enemy of God. Another god, perhaps, has pulled my arm back. When I saw poor Zopir, though, my religion didn’t have such a hold on me. The assassin’s duty called out to me, but humanity spoke to my frantic heart. Mahomet has furiously and tenderly reproached my weak senses now, and his grand, authoritative words have thickened my skin.

How powerful and terrible religion is! The fury in my heart has caught fire again. I am weak, Palmira, and this murder terrifies me. Holy rage has given way to pity, and I’m assailed by a multitude of confused feelings. I’m afraid of being a savage and afraid of being a blasphemer.

I don’t feel at all that I was born to be an assassin. But still, God commands me to do it, and I’ve made my promise. (Ibid.)

Seid and Palmira go to see Zopir who’s about to pray at the altar of his local gods. Zopir is resigned to the fact he will perish soon and perhaps, as he now knows, at the hands of his own child. He looks at them and says that he wishes to embrace his own children before he dies. They’re perplexed to hear such words but they ignore them. Zopir moved towards the altar to offer what could be his last prayer.

SEID: He runs to his false gods! It’s time to strike. 19Ibid., 83

SEID: Minister of death, I follow you. Show me the altar and guide my hand. (Ibid.)

Zopir walks behind the altar and Seid follows him. He pulls the sword and finally stabs Zopir. When Seid emerges from behind the altar, Palmira asks what happened.

SEID: I just obeyed…in utter misery. I grabbed him and dragged him by his white hair. Oh, Heaven! Wasn’t this crime what you wanted? I was trembling and seized with fear as I drove the blade consecrated for this murder into his breast. I wanted to strike again. This venerable old man cried out so wretchedly in my arms! Nature drew such great dignity and such moving features in his dying eyes that it filled my soul with tenderness and horror. I am deader than he is; I hate my life. 20Ibid., 85

Seid is overtaken with remorse. Phanor arrives at the scene where Zopir is bleeding to death. He yells that Seid killed his own father. Seid and Palmira are in shock at the revelation. Palmira also finds out that the one she loves is her own brother.

SEID: The love of my duty and nation, my gratitude and religion; everything that humans treat with the greatest respect inspired me to commit the most abominable of crimes. Please, place the dagger back in these savage hands. 21Ibid., 88

Zopir gets a chance to embrace them before his final breath and asks Seid to avenge him.

Omar walks in onto the scene and, and in a dirty trick, orders the arrest of Seid for having killed Zopir. Palmira and Seid are in disbelief since they all know that Mahomet ordered the killing. Mahomet intends to deceive the people of Mecca under the guise of bringing law and order.

Omar tells Mahomet that the people of Mecca are rising up at the news of the death of their leader. But those who believe in Mahomet are spreading the message that what happened is divine intervention against the infidel leader. He tells Mahomet that he had already denied any involvement in that crime and assures him that Seid is taken care of because they forced him to drink poison. Now Mahomet is free to pursue Palmira, unaware that she already found out the fatherhood secret.

In the following scene, Mahomet is standing before Palmira who launches accusations at him for being a savage and an impostor. She renounces his religion:

PALMIRA: What is this I hear? What laws, oh Heaven, and what generosity? I disown this blood-stained imposter forever.

[…]

Do you hear this clamor? My father pursues you from the shadows of death. The people are rising up and arming themselves in my defense. They will wrench the innocent from the insane. If I could I’d tear you apart with my own hands and watch your loved ones die, bathing in their own blood! May all of Mecca, Medina, and Asia punish such madness and hypocrisy! May all the world, ravaged and seduced by you, become ashamed of its chains, break them, and be free! May your religion, which engenders deceit be scorned eternally by future generations! May Hell, this place of pain and rage prepared for you alone, whose cries threatened anyone who doubted your disgraceful laws, be your well-deserved destiny! 22Ibid., 93

In the final scene, Seid is dying from poison. Palmira is hopeful that the crowd might kill Mahomet to avenge her father and her brother who was forced to drink poison.

Mahomet appears before the crowds and threaten great violence.

MAHOMET: If you learn to make criminal designs against me, infidels, then you must recognize my right to celestial vengeance. Nature and death have heard my voice. Death has obeyed me! Taking my defense it has left the imprint of my vengeance on this face that now turns pale. It is before your very eyes, ready to swoop down on you. And so shall my enemies feel my wrath. I’ll punish them for their foolish mistakes, their rebellious hearts, and their very thoughts. If you selfish people can make it to dawn alive, honor the pontiff whom you have to thank. Go to the temple now and appease my wrath. 23Ibid., 96

Out of fear while watching Seid in the throes of death, the crowd disperses. They seems to believe that it was an act of God. They embrace the new faith of Islam. When the crowd withdraws, Palmira realizes that her brother won’t be avenged. Rather than be a slave for Mahomet, she grabs the sword of Seid, she stabs herself and says:

PALMIRA: I’m dying. My eyes are blind to you now, hateful impostor. I die hoping that a more just god reserves a future for the innocent. You must reign; the world was made for tyrants. 24Ibid., 97

Mahomet is in grief over dead Palmira which drives him to a moment of regret about his role in killing a father and his children. Then he demands that people should not know about his crimes as he looks forward to ruling over humankind through deceit:

Mahomet: I must govern this imprisoned universe as a god: my empire is destroyed if the man is known. (Ibid)

Note: All the above controversial passages are available in the original language (French) on this page.

You might also like:

Candide: The shocking passages

Condemned by the French government and the Catholic Church: Read the controversial passages from Voltaire’s Candide (1759)

BOOK: CANDIDE

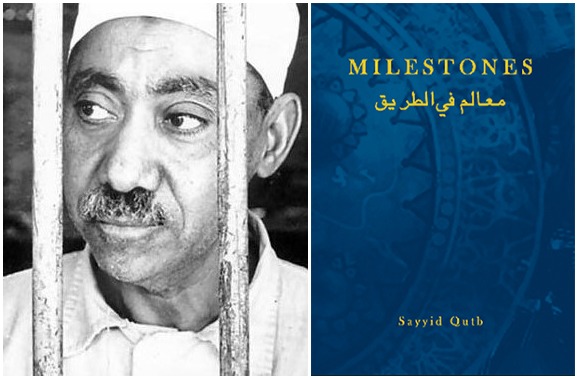

The jihadi manifesto: Sayyid Qutb’s Milestones

Summary and excerpts from the radical text that inspired terror attacks over the last 40 years

BOOK: MILESTONES

Endnotes