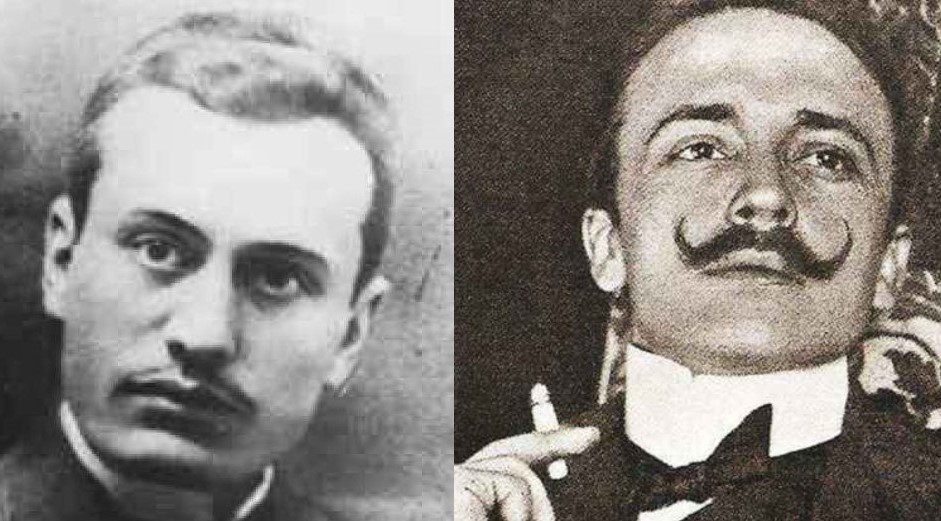

We tend to stereotype poets as sensitive souls, fragile creatures, who often struggle with inner conflicts. Perhaps that was true of many poets, but not Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. He was an Italian poet who founded an artistic and social movement called Futurism. He wanted to radically change the world as he saw it in the first decade of the 20th century. Marinetti envisioned a world where culture is militarized and industrialized, where government is autocratic and imperialistic, where men are revolutionary, strong and aggressive. If these ideas seem fascist to you, well, they were the seed that became Italian Fascism years later. In brief, he wanted generations of men who were fighters, not lovers!

In an article titled The Necessity and Beauty of Violence, Marinetti wrote:

[I]n the imaginations of our young people, we want to replace the tiresome Don Juan with dynamic, imposing figures such as Napoleon, Crispi, Ferrer, and Blériot. 1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 70.

Francesco Crispi was an Italian authoritarian stateman and a political strongman, a precursor for the fascist dictator Mussolini. Francisco Ferrer (1859–1909) was a Spanish radical anarchist, involved in riots and the attempt on the life of the Spanish king in 1906. He was eventually executed. He was viewed as a martyr by his supporters. Louis Blériot was a brave French aviator and inventor, credited with the first flight of an airplane between continental Europe and Great Britain in 1909. (Airplanes were a major “turn-on” for Italian Futurists.)

At that point in history, romantic love had long been the norm in forming relationships between men and women. It had been inculcated into their minds for centuries: Tristan and Isolde, Romeo and Juliet, the Sorrows of Young Werther, and countless others of operas, plays, novels, songs and poems dedicated to romantic love, that irresistible passion where lovers “fall” for one another. The kind of passion was not only at odds with Marinetti’s vision but, as he saw it, also a direct threat to young men!

But what is romantic love?

Marinetti’s target of disdain was not the love bond between brothers and sisters, or parents and children, but that gushy passion between lovers where they feel like they lost all control. Somehow that type of sweet fascination between men and women has become so dominant over the centuries that Western culture did not develop various terms to distinguish it from other “loves,” unlike, for example, ancient Greek civilization. What the Italian poet called amore could be literally translated simply as “love,” however that would be inaccurate. Hence you will find that term translated in English as “sentimentalism,” “sentimentalized love,” “romantic love,” “romance,” besides the all-too-vague “love.” Why Marinetti was so opposed to “romantic love”? His writings sheds light on the reasons:

1. Romantic love renders men weak!

The Italian poet who dreamt of nurturing strong young men found the mainstream view of love as a force beyond the lovers’ control as an obstacle to their maturity. That labelled that kind of “sentimentalism” as “the tyranny of love” or the “the sickness of love.” 2Ibid., 88.. In brief, he saw love as unhealthy:

Everyone suffers, becomes depressed, exhausted, imbecilic, under the dictate of a fearful deity that must be overthrown: namely, Sentimentalism. 3Ibid., 55.

2. Romantic love is a delusion but sex is useful!

A romantic relationship combines both the emotional (love) and the physical (lust) into one union. Though many lovers prefer to see their bonds as purely puritanical, “sexual attraction” is always be part of romance. Is that so bad? Well, according to Marinetti, yes!

We are convinced that love—sentimentalism and lust—is the least natural thing in the world. Only coitus, the purpose of which is the futurism of species, is natural and important. 4Ibid.

Marinetti proposed to reduce love to just a bodily function, like eating and drinking:

The whole enormous business of romantic love is thus reduced to the single purpose of preservation of the species, and physical arousal is at last freed from all that its titillating mystery, from relish for the salacious and from the vanity of Don Juanism; it becomes merely bodily function, like eating and drinking. 5Ibid., 58.

3. Romantic love at its core is a money-making machine

Perhaps Marinetti is not alone to note that behind the propagation of the idea of romantic love, there is multi-billion dollar businesses selling music, film, flowers, postcards, chocolate and teddy bears!

Love—romantic obsession and sensual pleasure—is nothing but the invention of poets, who made a present of it to mankind… And poets will retract it as one takes back a manuscript from the hands of a publisher who has shown that he is incapable of publishing it decently. 6Ibid., 55.

4. Romantic love distracts men from achieving higher purposes

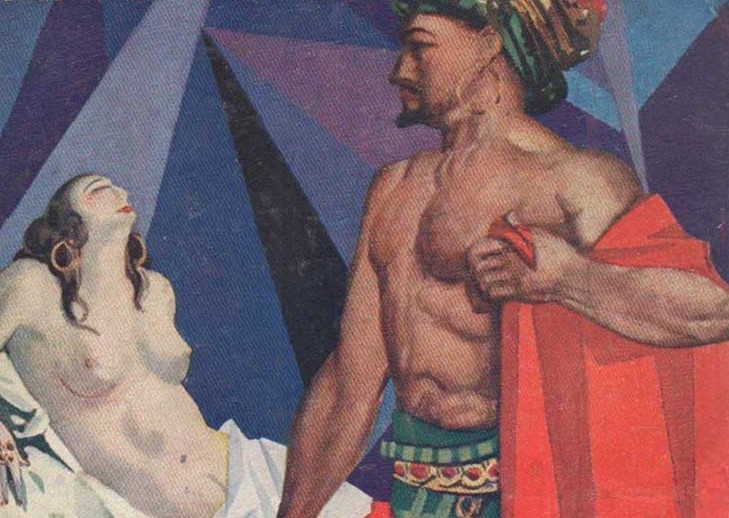

Marinetti saw men as revolutionary fighters. Heroes in pursuit of noble missions would not be involved in romantic relationships. In his controversial novel, Mafarka, Marinetti speaks through his main character who would rededicate his life to a great mission:

Love, women…[…] I have erased these things from my memory!7Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Mafarka the Futurist: An African Novel, trans. Carol Diethe and Steve Cox (London, United Kingdom: Middlesex University Press, 1998), 40.

Note that both love and women are two sides to one worthless coin in the author’s writings. It is not surprising to realize that Mafarka is probably one of the most misogynist novels ever written.

5. Romantic love belongs to the past and the past is dead!

Marinetti took the matter of “romantic love as an outdated idea” seriously enough that he listed it as an official objective on the agenda of the Futurist political party in 1919:

Our immediate objective was to fight tooth and nail against the most repugnant forms of Italy’s obsession with the past: archaeology, academicism, senility, quietism, cowardice, pacifism, pessimism, nostalgia, sentimentalism, obsession with romantic love,[emphasis added] foreign-owned industries, and so on. 8F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 277.

Marinetti: “To Hell with the tango!”

Marinetti saw that the courtship game to win romantic love had taken many shapes, one of them is dance. At the time of writing the foundational material for his Futurist movement, in the early years of the 20th century, the tango craze had been spreading around the Western world. He despised that “sexy” dance so much that he dedicated an entire article against it in 1914:

To Hell with the tango! For the sake of our Health, our Strength, our Will, and our Virility. 9Ibid., 133.

He was revolted by that dance because it allows women to yield a seductive power over men. In his familiar shocking language, he mocked the dance:

Possessing a woman isn’t rubbing yourself up against her but penetrating her. Barbarian!

One knee between her thighs? Come on, you need two! Barbarian!

Fine, yes, we are barbarians! Down with the tango and its cadenced swoons. Are you really convinced there’s a lot of pleasure to be had, gazing into each other’s mouths and ecstatically examining each other’s teeth, like a pair of hallucinating dentists? Jerk… Swoop… So, do you really find pleasure in desperately bending over each other, uncorking your love lusts, each in turn, without ever quite getting there?… or staring at the toes of your shoes, like hypnotized cobblers?… O dearest heart, do you really take a size 35?… What lovely shoes you’re wearing, my dreamchild!… And you toooo!… 10Ibid., 132.

Murdering the moonlight!

Romantic love was a key component in several art movements that preceded the founder of Futurism. That explains why he harshly criticized both Symbolism and Romanticism. Artworks of these movements aimed to evoke strong emotions in the viewer or reader. One of these emotions, for which Marinetti had no use, was love. He was opposed to Europe’s favorite writers and poets who were associated with such art schools. He mocked namely three French Romantic poets: Théophile Gautier (1811-1872), Alfred de Musset (1810-1857) and the great Victor Hugo (1802-1885) 11Ibid., 132..

To Marinetti, the “moonlight” was a symbol that stood for the artistic baggage of European poets and artists of the previous centuries, and what it is deserved is to be “destroyed”!

Let us kill the moonlight!

And so it was that three hundred electric moons, with their rays like dazzling white chalk, snuffed out the gree, antique queen of all loves [the moonlight]. 12Ibid., 28.

Above, he does not only want to “kill the moonlight” but replace it with the most appropriate symbol, which he admired, from the Industrial era: electric light.

In an article titled, “We Renounce our Symbolist Masters, the Last of All Lovers of the Moonlight”:

[A]fter having loved them intensely, we hate the glorious forefathers of our intellects, the great Symbolist geniuses, Edgar Poe, Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Verlaine. Today we feel nothing but contempt for them. […]

For those geniuses, there was no poetry without nostalgia, without evocation of times that were dead and gone, without the mists of history and legend.

We detest them, the Symbolist masters. 13Ibid., 43.

To murder the moonlight was not only to destroy sentimental poetry, art, and theatre, but in a sense, destroy the past—traditional culture and institutions—which was explicitly a goal by the Futurist movement.

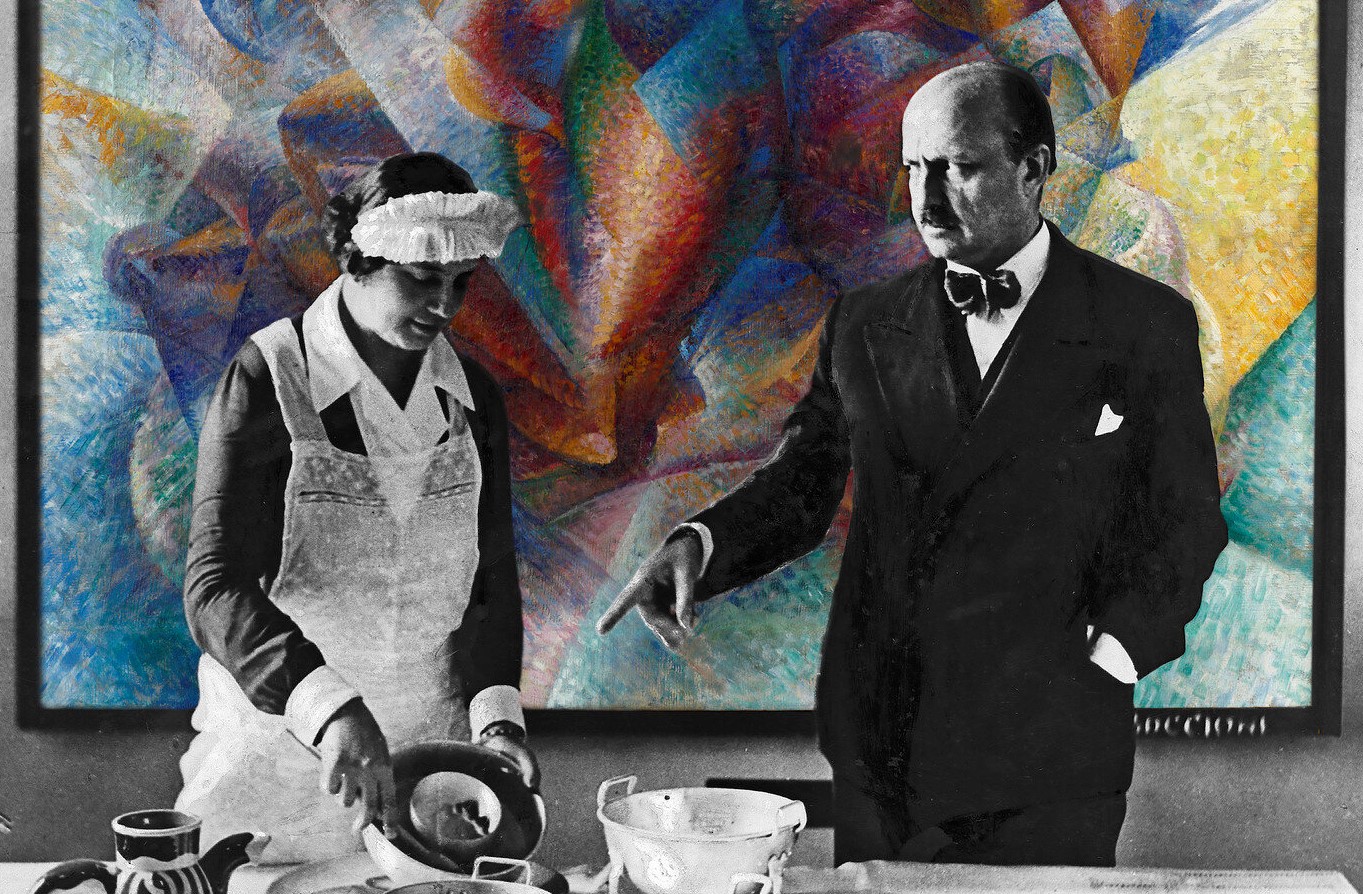

The greatest irony about Marinetti’s rejection of poetic language and romantic praise of women, is that he used it but towards another “object,” that is machines. In fact, he spoke about “the machine” as if it’s the beloved of the Futurist man who deserves his attention and the occasional caresses!

You might also like:

Mafarka: Summary & analysis plus all the controversial passages

Read the obscene parts of the first two chapters that sent the Italian author to court

BOOK: MAFARKA THE FUTURIST

The misogynist who supported feminist causes—mostly inadvertently

The Italian Futurist poet, F. T. Marinetti, was a misogynist and a proto-feminist all at once

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

‘Destroy museums!’–Why an Italian waged war against the past

Those who embraced state-sponsored iconoclasm as a fast track to modernization

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Was Futurism proto-fascism?

The most important elements of Fascism could be traced to Italian Futurist writings years earlier

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes