Below is a timeline of an alliance between two men that probably changed history. They influenced one another to the point that the ideological story of one can never be told in isolation of the other. One started an artistic and social vision and meant to bring it into politics, whose name is F. T. Marinetti. His vision, called Futurism, propagated fascist ideas before it became an organized movement. The other, Benito Mussolini, started as a socialist journalist, then ended up as a fascist dictator. Many of Mussolini’s ideas, which make up fascism as we recognize it today, were inspired by Marinetti. To the disappointment of Marinetti, Mussolini at the peak of his power would keep his distance from his fellow revolutionary. These two men enjoyed a cult of personality in their own spheres, so much so that their deaths meant the definite end of the two popular movements they led. Here is the timeline of their uneasy relationship:

1876

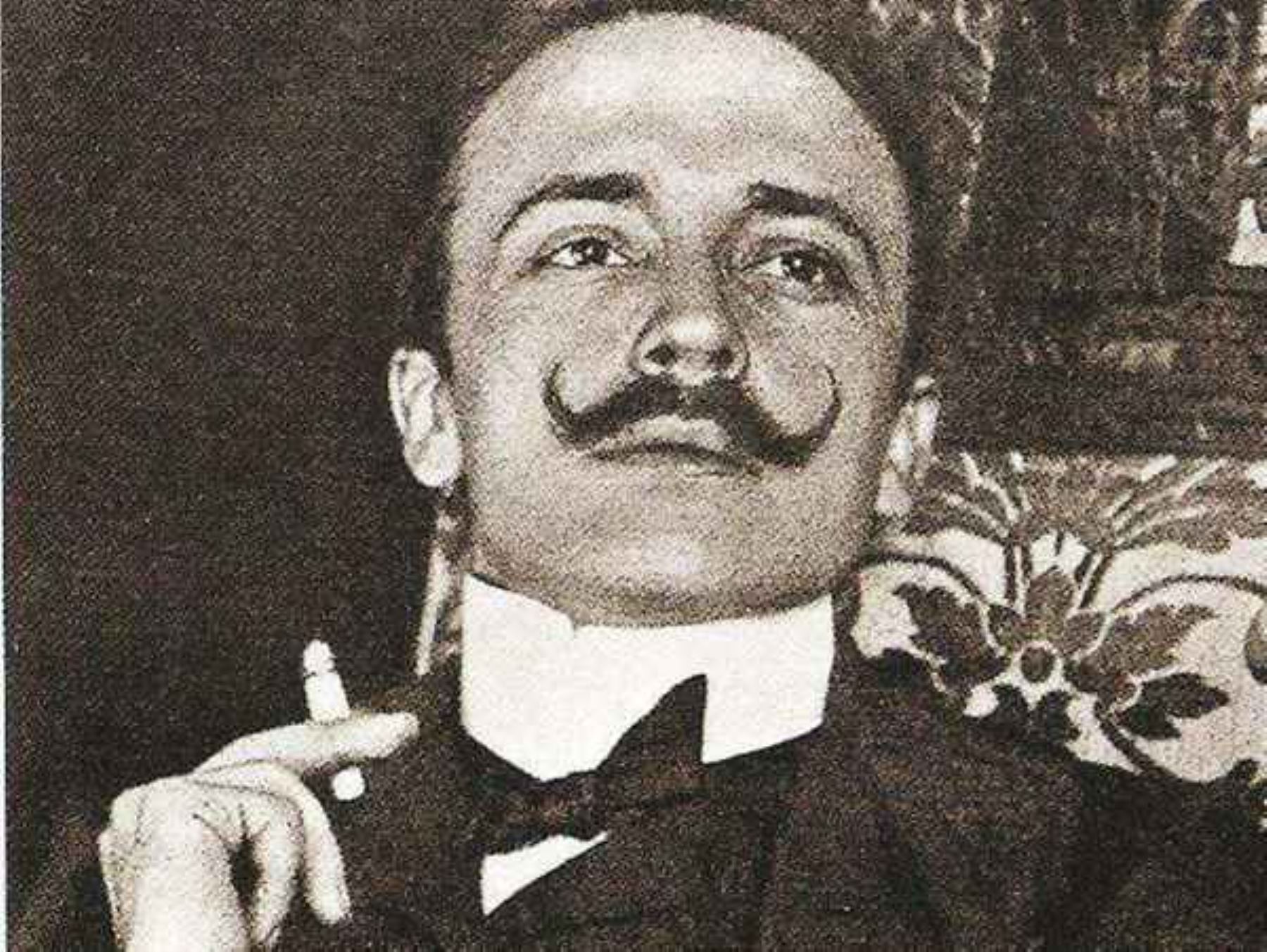

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the Italian writer and poet, was born in Alexandria, Egypt to an Italian family.

1883

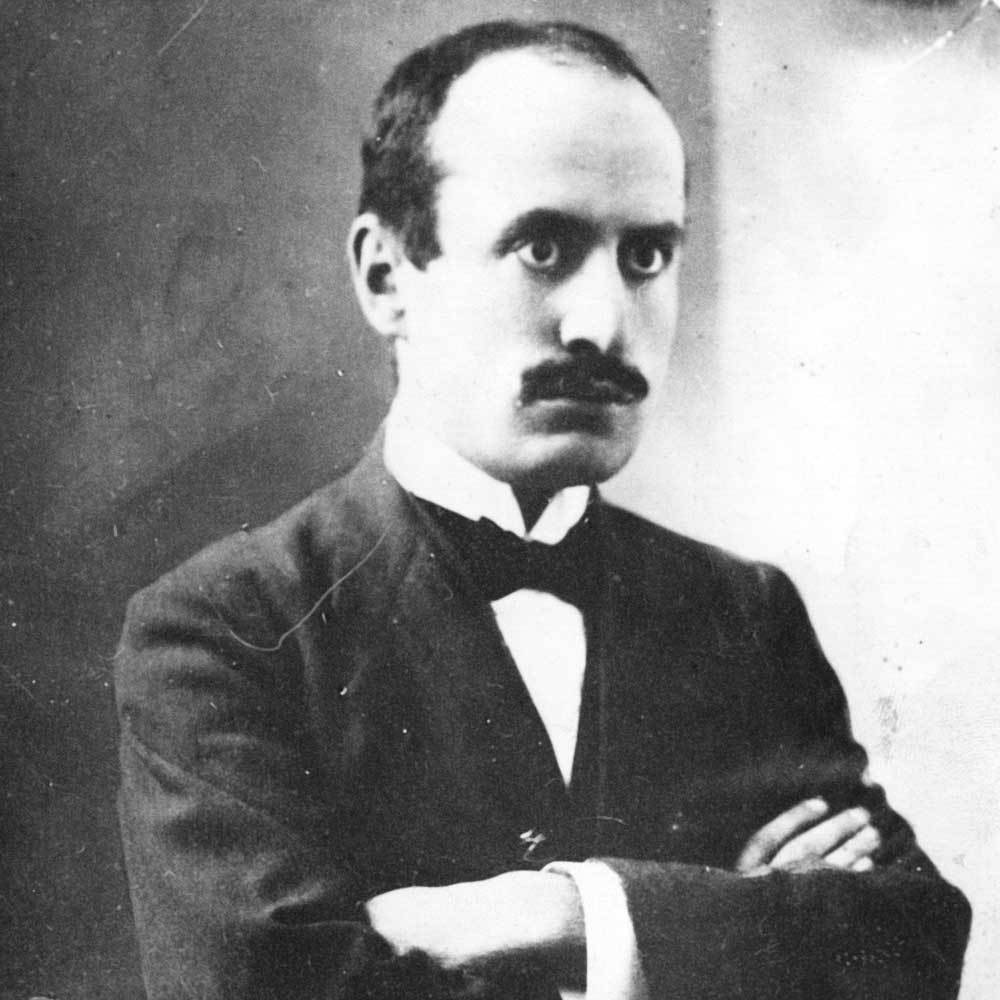

- Benito Mussolini, Italy’s fascist dictator and its longest-serving prime minster, is born in a small town called Predappio, in the northeast of Italy. His father was a socialist and little Benito was brought up with socialist convictions.

1901

- Mussolini graduates and becomes an elementary schoolmaster. He also becomes officially a revolutionary socialist who writes regularly in periodicals.

1902

- Mussolini fled Italy to avoid the military service. He continued writing for socialist periodicals and calling for a violent revolution while living in Switzerland. Socialists at that time viewed the “bourgeois” conflicts between European powers as a disgrace that should stop since working class members of all nations fight for the same cause.

- Meanwhile Marinetti who had graduated with a law degree two years earlier has abandoned his father’s dream of being a lawyer, and is now on a successful path as a poet, in French and Italian. For years to come, he would publish poetry collections.

1904

- After joining violent strikes, Mussolini is arrested and deported back to Italy. During that period, in both Switzerland and Italy, he was arrested and imprisoned several times.

1905

- Back in Italy, Mussolini is a military deserter and can only be pardoned if he enlists. So he’s forced to serve two years in the military.

1909

- The poet Filippo Marinetti publishes on the front page of the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro the Futurist manifesto that is meant to revolutionize all aspects of life: artistic, cultural, moral, economic and political.

- Mussolini, who considered himself a socialist intellectual, probably also learnt about Futurism at this point as it became a dominant art and social movement. Most likely, he was intrigued by its proto-fascist ideas of glorification of industrialization, technology and war. (Read analysis here).

- Meanwhile the 26-year-old Mussolini is becoming one of Italy’s most important socialists. He publishes a semi-pornographic and anti-clerical novella called The Cardinal’s Mistress.

1912

- Mussolini is the editor of Avanti! (meaning “Forward!”), the official newspaper of Italy’s socialist party.

1914

- World War I starts. Italy remains neutral.

- The Futurists are opposed to neutrality.

- Mussolini goes against the official socialist line and supports the war too. Mussolini is expelled from the socialist party due to his stance. The year WWI started was the turning point for Mussolini from the extreme left towards fascism. He and a number of former socialists establish the new Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (“Italian League of Combat”) which supports the war. Eventually, it would become the National Fascist Party, from 1921.

1915

- Italians are divided on whether they should join the war. Socialists, liberals and Catholics are on one side. An Interventionist side emerges where conservatives, nationalists and futurists call for joining the war on the side of the Allies, with Britain, France and Russia. The Interventionists saw the Great War as an opportunity to transform Italy into a powerful nation and to rise up against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. They stage together anti-neutralist demonstrations.

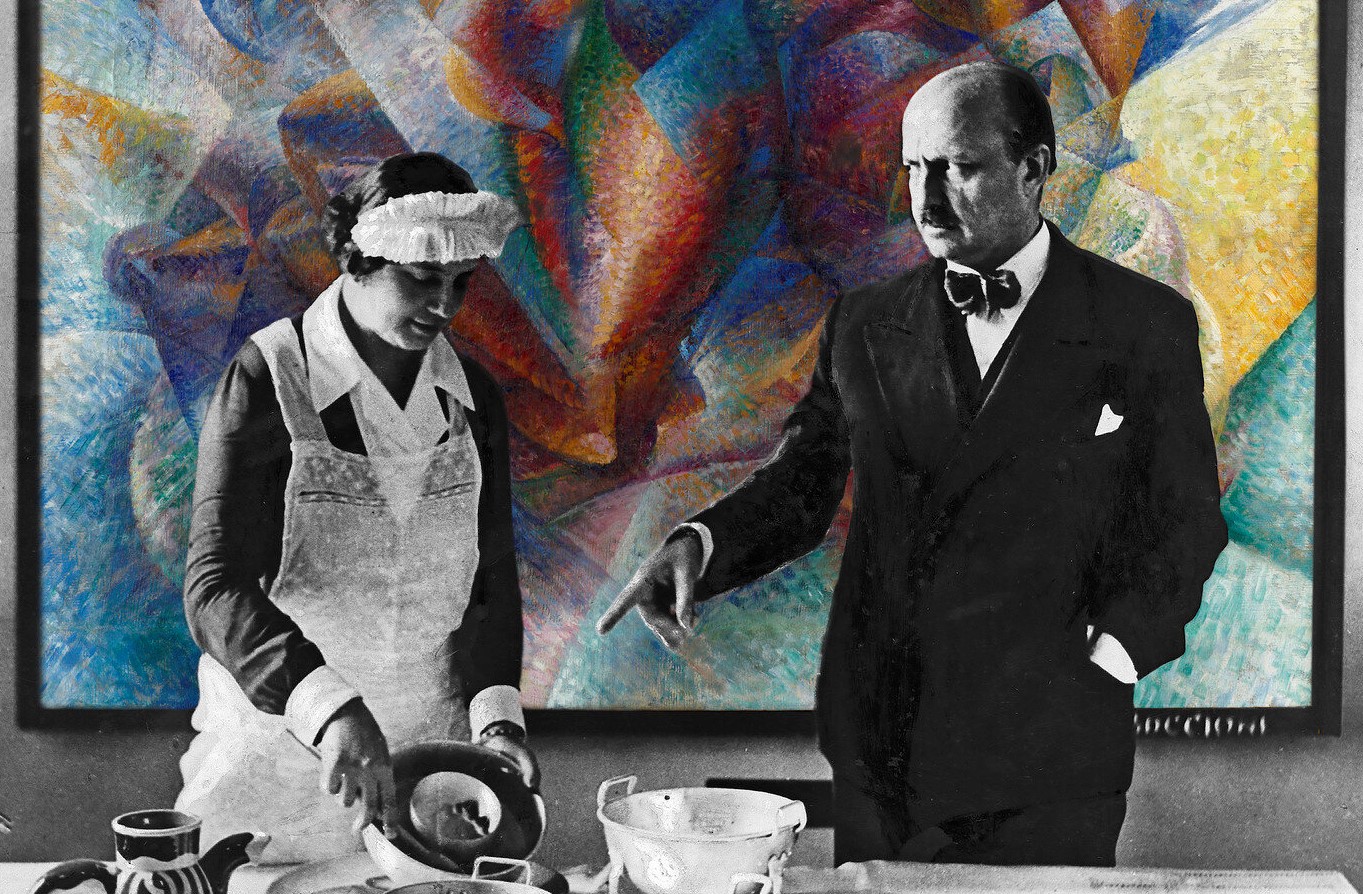

- Accused of collaborating to organize interventionist demonstrations in Rome, Marinetti and Mussolini are arrested together along with others.

- Nine months later, in May, Italy finally joins the war (WWI).

His recent actions, his attitudes and his rebellion are clear demonstration of a Futurist consciousness. […] Mussolini was always, like Corridoni [a revolutionary syndicalist and a friend of Mussolini], a warm supporter of ours. […] The absolutely lightning speed with which he was converted to the need for war and the virtues of war can be taken as a first point in support of my argument. You must, however, bear in mind the new propaganda system he has adopted—a system which is ours and that we activated. 1F. T. Marinetti: Critical Writings, trans. Doug Thompson, ed. Günter Berghaus (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006), 242.

1918

- World War I ends. The return of war veterans to civil society in Italy gives rise to several political movements.

- One of the veterans was the poet Filippo Marinetti. He founded the Partito Politico Futurista, or Futurist Political Party.

- The Futurist Political Party is approached by the prominent ex-socialist Benito Mussolini. He is a supporter of their cause and whose paper, Il popolo d’Italia becomes an occasional outlet for announcements by the Futurists and their affiliates.

1919

- The Futurist Political Party is absorbed into the Italian Fascist Party (Fasci Italiani di Combattimento), which was established by Mussolini in 1914. Marinetti had been among the earliest to show support for the Fascist Party.

- Filippo Marinetti co-writes with the revolutionary syndicalist leader, Alceste De Ambris, the Manifesto of the Italian Fasci of Combat, commonly known as the Fascist Manifesto. That is the founding manifesto of Italian Fascism.

- Mussolini declares that he’s a supporter of Futurism. Marinetti admired Mussolini and probably found him the perfect embodiment of his ideas. (Note: Defenders of the Futurist founder claim that at that point, members of the Fascist party included members from a variety of political affiliations including even socialists. That is true however that does not negate the fact that most fascist ideas today as we understand them, were originally rooted in Futurism.)

- Marinetti and Mussolini speak together in rallies for the general elections of Italy.

- The results were a huge disappointment to the Fascists, and their Futurist supporters. They received only 1.7% of the votes of Milan.

1920

- Marinetti becomes disillusioned with politics after the 1919 miserable defeat in politics. Following the election, Marinetti breaks off with Mussolini but his support for him would never stop, at least officially. In reality, Marinetti would never cease to feel uneasy about the Futurist union with the fascists. Marinetti was also appalled by Mussolini’s turn to the right on several issues, one of which was anti-clericalism. Mussolini’s appeasement of the conservative factions was obvious in his flirting with the Church and the monarchists. His opposition to them was softening at this point. Marinetti considered some of his policies reactionary. Marinetti was also concerned about the first signs of a personality cult Mussolini was nurturing.

- Marinetti resigns from the Central Committee and quit the Fascist party. Frustrated with the evaporated dreams of his Futurist political career, he decides to focus on his work as a founder of an artistic movement—exhibitions, tours and evening gatherings. However, he continues to be an important associate of the fascist party, whose ideological influence never disappeared though it slowly diminished. (Eight years later, they would give him a job. View below.)

1922

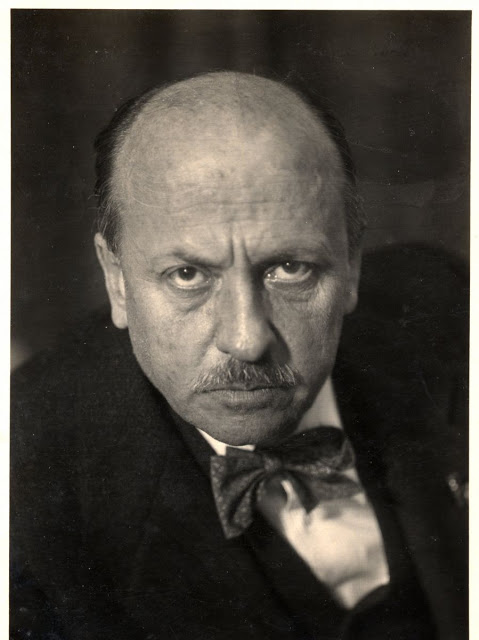

- Mussolini’s failure in the elections of 1919, his pre-formed ideas over the years and the political turmoil of the period, drive him to reject the entire parliamentary system and to consider seizing power by force. In a coup d’état, known as the March on Rome, Mussolini, followed by 30,000 supporters, commonly referred to as the blackshirts, installs himself as the Prime Minister and head of state.

- By that time, Marinetti sees that Mussolini has made the Fascist party into a reactionary one. The Fascist anti-intellectualism and censorship are starting to worry Marinetti who realizes he needs to cooperate somehow.

1923

- Marinetti and other Futurists pay lip service to the fascists in order to protect their careers as artists. Marinetti wrote the Manifesto to the Fascist Government (excerpts below), where he almost “begs” the fascists to reserve artists some cultural space to continue their activities, while assuring them that he gave up on his political ambitions. Mussolini barely cares about “a bunch of artists” who used to be his associates from his younger years

- All Marinetti’s attempts to make Futurism the official art style of the state fail. He has to accept the division of politics and art. At that point, the Futurists (ironically, considering many of their views) were treated as on the left end of the cultural spectrum. They were initially tolerated by the conservative cultural elite, as one of several modern movements. Over the years, they were marginalized, and so was their leader, even though, under the dictatorship of Mussolini, they had long stopped acting like radical revolutionaries.

Marinetti assured the Fascist government he was no longer interested in politics:

[Futurism] is unequivocally an artistic and ideological movement. It becomes involved in politics only in time of grave peril for the Nation. 2Ibid., 357.

In the same manifesto, he praised Mussolini:

Prophets and pioneers of the great Italy of today, we Futurists are only too happy to applaud in our not yet forty-year-old prime minister, a wonderful Futurist temperament. 3Ibid., 358.

He would continue for years to bring up Mussolini’s early support for Futurism. But Mussolini had no longer a use for the Futurists. Mussolini mostly ignored them. Elsewhere in the same manifesto, Marinetti declares:

With Mussolini, Fascism has rejuvenated Italy. 4Ibid.

Then Marinetti presented his plea for cultural protection:

It is his task to help us bring new life to the world of art, which is still dominated by obnoxious people and organizations. 5Ibid.

1928

- Although Futurism is on the margins, and clearly not a favorite art style by Il Duce, Marinetti is not completely ignored. He is given the position of the secretary of the Fascist Writers’ Union and became a member of the conservative Royal Academy. Indeed, the man who spent years calling for the destruction of old institutions and academies becomes one of their card-carrying members.

1929

- Mussolini forms an alliance with the Papacy resulting in the papal recognition of the Fascist government, while leaving the pope a sovereign state in the heart of Rome.

1931

- That year marks the beginning of Marinetti’s slow return to the Catholic Church. He, who was anti-Catholic, decides to eventually re-join the Church. The decision is probably influenced by the political atmosphere.

1937

- For Futurism, things were to take a turn for the worse, when in 1937, as the relationship between Mussolini and Hitler started warming. The cultural establishment was influenced by the Nazi government and Futurist art was no longer welcome. The Fascists would view it as “degenerate art,” the label Nazis threw at most modern art.

1938

- Marinetti successfully convinces Mussolini to not allow the travelling German exhibition of “degenerate art” to enter Italy.

- Marinetti also condemns publicly antisemitic policies and tries to prevent their import from Nazi Germany into Italy. It should be noted that even though Marinetti glorified violence in his writings, he never called for violence towards any group of people and he was consistent during his life in his opposition to antisemitism.

1939

- His published condemnation of the verbal attacks on modern art leads to the shutting down of the Futurist paper Artecrazia in 1939. Being a life-long supporter of Mussolini, associated with the Church, or a member in a conservative Italian academy did not help him gain back any of his former or dreamed-of glory.

1940

- Italy enters World War II on the side of Germany.

1943

- Italy is defeated. King Victor Emmanuel III removes Mussolini from office and places him under house arrest.

- Mussolini is captured by the Allied Powers.

1944

- Marinetti dies at the age of 67. Marinetti’s death brings the end to Italian Futurism.

1945

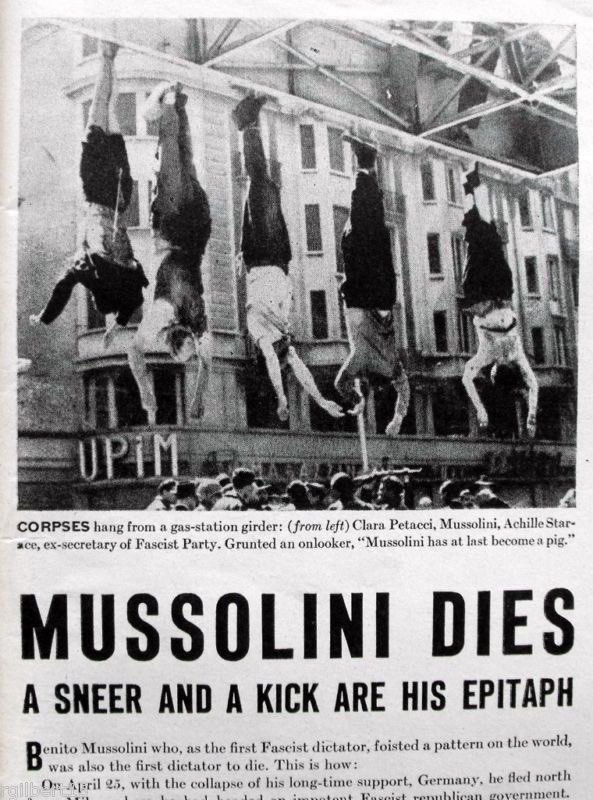

- Mussolini and his mistress are captured by members of an Italian resistance movement and executed by firing squad. After 21 years of rule in government, Mussolini’s execution draws the curtain on Italian fascism.

You might also like:

Gloriously masculine and mechanical: The Futurist Manifesto

The three themes of their manifesto show how the Futurists envisioned the modern world a century ago

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Was Futurism proto-fascism?

The most important elements of Fascism could be traced to Italian Futurist writings years earlier

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

‘Destroy museums!’–Why an Italian waged war against the past

Those who embraced state-sponsored iconoclasm as a fast track to modernization

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Three possible reasons why Italy lagged behind Europe for centuries

Why Italy’s modernization has been, and continues to be, problematic?

ARTICLE: THE FUTURIST MANIFESTO

Endnotes