A Farewell to Arms (1929) is a powerful war story and love story, intertwined. Neither story was without controversy when the book was published. The love story contained enough sexual content, albeit implicit, to prompt condemnation and censorship. The war story was so true to history that the Italian government banned it upon publication from 1929 to 1948. Hemingway’s depiction of the humiliating defeat of the Italian army at the battle of Caporetto was not the only reason. There was also its anti-military content which Italian censors would not accept.

It has also been said that the personal contempt from Hemingway towards Mussolini and fascism in general, both derided publicly by the author, were behind the banning of his work by Il Duce himself. Fernanda Pivano, an Italian writer and translator was arrested in 1943 for illegally translating the novel.

WWI’s catastrophic battle of Caporetto, October 1917, was a national disgrace in Italy. The Italian army was defeated by Austrians and was forced into a retreat. Only days after its first anniversary, in October 1918, the Italians won at Vittorio Veneto, which was considered the final victory over the Austrians. That victory brought the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the end of the First World War on November 4, 1918.

Hemingway portrayed Italians as disillusioned with the war. Even throughout their retreat, he showed them as disorderly, cowardly and incompetent. Early on, in the novel, we encounter the first example of the disillusioned Italians. The American protagonist, Frederic Henry, serves as a lieutenant (“tenente”) among other ambulance drivers during WWI and throughout he reports how they felt about it. They show no respect for the fighting soldiers and believe that Italy should withdraw.

“I know it is bad but we must finish it.”

“It doesn’t finish. There is no finish to a war.”

“Yes there is.”

Passini shook his head.

“War is not won by victory. What if we take San Gabriele? What if we take the Carso and Monfalcone and Trieste? Where are we then? Did you see all the far mountains to-day? Do you think we could take all them too? Only if the Austrians stop fighting. One side must stop fighting. Why don’t we stop fighting? If they come down into Italy they will get tired and go away. They have their own country. But no, instead there is a war.”

“You’re an orator.”

“We think. We read. We are not peasants. We are mechanics. But even the peasants know better than to believe in a war. Everybody hates this war.”

“There is a class that controls a country that is stupid and does not realize anything and never can. That is why we have this war.”

“Also they make money out of it.”

“Most of them don’t,” said Passini. “They are too stupid. They do it for nothing. For stupidity.” 1Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929; reprint, New York: Harper Perennial, 2014), 50.

Henry develops a warm friendship with an Italian priest. As the war keeps taking one bad turn after another, one time they had a conversation where both expressed doubts about victory. The priest says:

“I hoped for a long time for victory.”

“Me too.”

“Now I don’t know.”

“It has to be one or the other.”

“I don’t believe in victory any more.”

“I don’t. But I don’t believe in defeat. Though it may be better.”

“What do you believe in ?”

“In sleep,” I said. 2Ibid., 173-174.

“His belief in sleep” is Henry’s way of saying he has become indifferent to religion and grand concepts of victory and heroism. That indifference is clear in another passage:

I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious, and sacrifice and the expression in vain.[…] Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates. 3Ibid., 179.

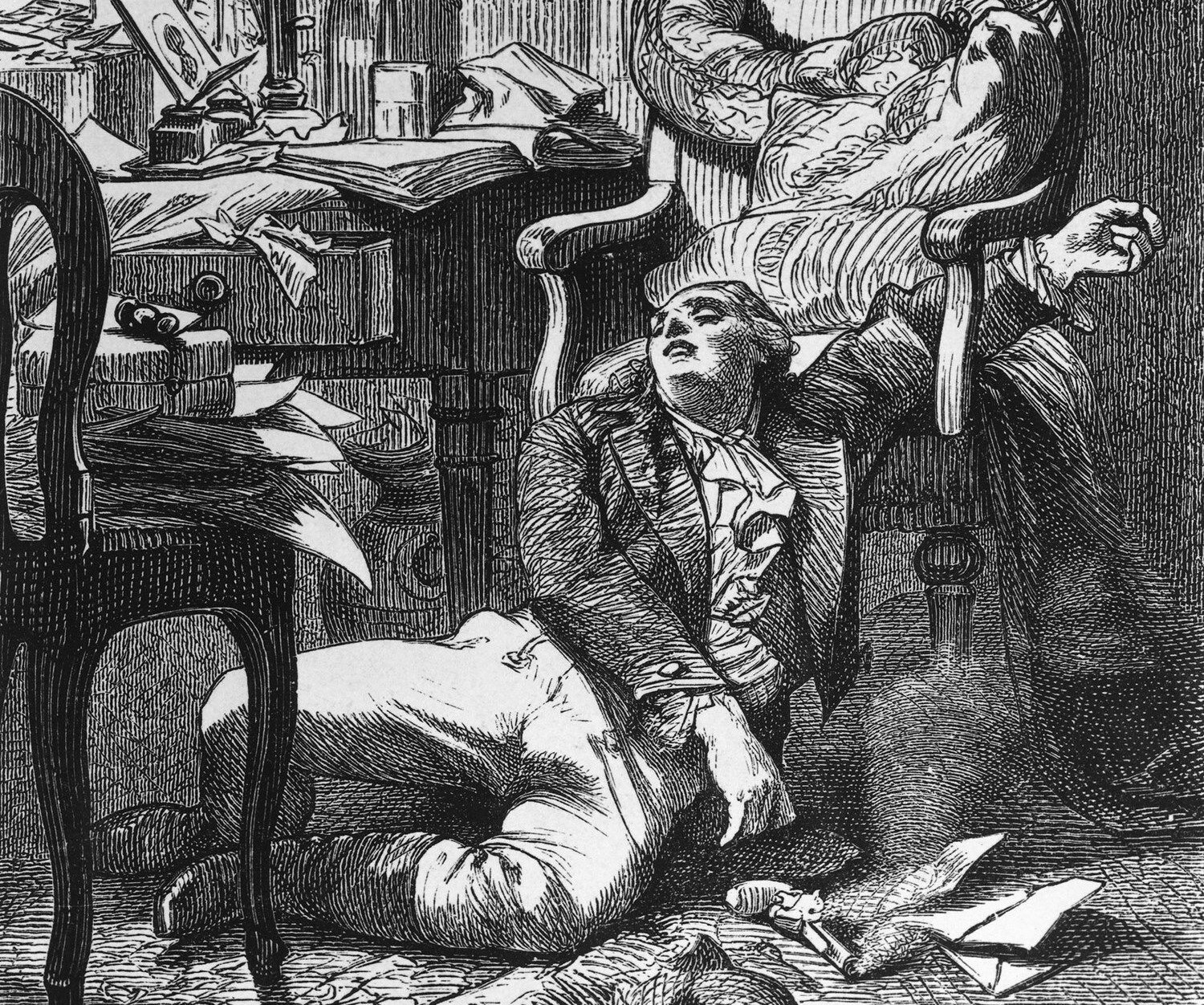

The war event depicted in the book which was the main reason the book was banned was the retreat of Italians soldiers. In the novel, the soldiers learn that the front lines have been broken by the enemy and they were ordered to retreat. This event is known historically as the Battle of Caporetto.

The next night the retreat started. We heard that Germans and Austrians had broken through in the north and were coming down the mountain valleys toward Cividale and Udine. The retreat was orderly, wet and sullen. In the night, going slowly along the crowded roads we passed troops marching under the rain, guns, horses pulling wagons, mules, motor trucks, all moving away from the front. There was no more disorder than in an advance. 4Ibid., 182.

Although the retreat was initially orderly, that was not to last.

Throughout the retreat, Italians are depicted as incompetent and indifferent. Italian ambulance drivers, Bonello and Aymo make the following remarks:

“I like a retreat better than an advance,” Bonello said. “On a retreat we drink barbera.”

“We drink it now. To-morrow maybe we drink rainwater,” Aymo. 5Ibid., 186.

Aymo’s response above foreshadows his own death the following day in the rain.

During the retreat, one of the ambulance vehicles gets stuck in the mud. Two sergeants who were riding in it start walking off. Henry orders them to stop and help but they refuse. He starts shooting at them. One is injured. Bonello asks to “finish” it off. He goes to the sergeant and shoots him dead. Then the bitterness among the ranks of hierarchy in the Italian army is laid bare (note the obscene F word was removed from print by the American publishers):

“I killed him,” Bonello said. “I never killed anybody in this war, and all my life I’ve wanted to kill a sergeant.”

“You killed him on the sit all right,” Piani said. “He wasn’t flying very fast when you killed him.”

“That’s one thing I can always remember. I killed that — of a sergeant.” 6Ibid., 200.

It should be noted that this is the first time the protagonist, Henry, uses his gun and ironically firing at someone from his own side. To make matters worse, it’s an American (read: a foreigner) shooting at an Italian sergeant.

When they get stuck in the mud again, Henry, Aymo, Piani, and Bonello abandon their cars and walk along a railroad track. They see German soldiers on bicycles from whom they try to duck out of sight. The Germans see them but ignore them. They avoid the main road and take a secondary one. All of a sudden they get shot at and Aymo is killed instantly.

Bonello shook his head. “Aymo’s dead,” he said. “Who’s dead next, Tenente? Where do we go now?”

“Those were Italians that shot,” I said. “They weren’t Germans.”

“I suppose if they were Germans they’d have killed all of us,” Bonello said.

“We are in more danger from Italians than Germans,” I said. “The rear guard are afraid of everything. The Germans know what they’re after.” 7Ibid., 207.

From that point on, the retreat was turning chaotic. They realize it couldn’t have been the Germans who fired at them. Panicky, incompetent Italian rear guard are shooting at their own compatriots. That scene highlights the confusion and terror of war, which the author elaborates on after:

The Italians were even more dangerous. They were frightened and firing on anything they saw. Last night on the retreat we had heard that there had been many Germans in Italian uniforms mixing with the retreat in the north. I did not believe it. That was one of those things you always heard in the war. It was one of the things the enemy always did to you. You did not know any one who went over in German uniform to confuse them. Maybe they did but it sounded difficult. I did not believe the Germans did it. I did not believe they had to. There was no need to confuse our retreat. The size of the army and the fewness of the roads did that. Nobody gave any orders, let alone Germans. Still, they would shoot us for Germans. They shot Aymo. 8Ibid., 209.

Later on, Piani, one of the Italian ambulance drivers reveals his feelings as well as those of other drivers, and perhaps soldiers too:

“You see we don’t believe in the war anyway, Tenente.” 9Ibid., 210.

After the retreat, the soldiers mistakenly think the war is over. That’s when they confess their true feelings about the war:

“Viva la Pace!” a soldier shouted out. “We’re going home!”

“It would be fine if we all went home,” Piani said.

“Wouldn’t you like to go home?”

“Yes.”

“We’ll never go. I don’t think it’s over.”

“Andiamo a casa!” a soldier shouted.

“They throw away their rifles,” Piani said. “They take them off and drop them down while they’re marching. Then they shout.”

“They ought to keep their rifles.”

“They think if they throw away their rifles they can’t make them fight.”

In the dark and the rain, making our way along the side of the road I could see that many of the troops still had their rifles. They stuck up above the capes.

“What brigade are you?” an officer called out.

“Brigata di Pace” some one shouted. “Peace Brigade!” The officer said nothing.

“What does he say? What does the officer say?”

“Down with the officer. Viva la Pace!”

“Come on,” Piani said. 10Ibid., 212.

Next Henry encounters another dangerous scene. The Italian army police is rounding up officers and shooting them for deserting their troops. He watched a confrontation followed by an execution:

“It is you and such as you that have let the barbarians onto the sacred soil of the fatherland.”

“I beg your pardon,” said the lieutenant-colonel.

“It is because of treachery such as yours that we have lost the fruits of victory.”

“Have you ever been in a retreat?” the lieutenant-colonel asked.

“Italy should never retreat.” 11Ibid., 216.

Eventually Henry is reunited with his beloved Catherine. He complains that he feels like a criminal for abandoning his duty:

“I feel like a criminal. I’ve deserted from the army.”

“Darling, please be sensible. It’s not deserting from the army. It’s only the Italian army.” 12Ibid., 243.

Ouch! Yet another joke at the expense of the Italian army who suffered greatly in their battle against Austrians in WWI.

The above is one of two articles on A Farewell to Arms. The other article features all the dirty words you won’t find in the novel.

You might also like:

A Farewell to Arms: The dirty words you won’t find in the novel

Hemingway’s work was banned despite replacing the “vulgar” words with dashes

BOOK: A FAREWELL TO ARMS

Madame Bovary: The scandalous scenes

Why Gustave Flaubert was put on trial for Madame Bovary?

BOOK: MADAME BOVARY

Endnotes