Women today could be seen enjoying books on buses, on trains and in public parks—is there a problem with that? For many decades there was. During the 18th and 19th centuries, men were concerned about fictional books proliferating among the hands of their wives and daughters. There is no better novel for a complete picture of how society viewed women who read fiction than Gustave Flaubert’s masterpiece, Madame Bovary of 1857.

Madame Bovary is a story of a desperate wife who is so dissatisfied with her husband and domestic life that she starts having affairs. The adulterous liaisons are inspired by ideas from romance books she had been reading since her teenage years. She wastes her husband’s money on shopping for herself and for her lovers. When she realizes she brought financial ruin to her family, and that there is no viable end to her miserable marriage, she commits suicide. One of the underlying themes throughout the book is her failure to reconcile the romantic fantasies of books with her own reality.

We’re told early on of her disappointment with her life and her hunger for one similar to that in fiction:

Before her wedding-day, she had thought she was in love; but since she lacked the happiness that should have come from that love, she must have been mistaken, she fancied. And Emma sought to find out exactly what was meant in real life by the words felicity, passion and rapture, which had seemed so fine on the pages of the books. 1Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary: Provincial Lives, trans. Geoffery Wall (London and New York: Penguin, 1992), 33.

She grew up in a convent where there were regular readings of the Bible and other religious books. She was a voracious participant. This kind of books is, of course, safe for girls. But even then, there were signs that young Emma was different. It’s unusual but not alarming that she was more interested in church books than in church services. However, even with church books, she was more fascinated with sensual imagery, rather than appreciate them for their purely spiritual value:

Instead of following the mass, she would gaze in her book at the pious vignettes with their azure borders, and she loved the sick lamb, the Sacred Heart pierced by sharp arrows, [the lamb and the Sacred Heart are symbols of Jesus] or poor Jesus, sinking beneath the weight of his cross. 2Ibid.

Romantic poetry was also one of her reading interests such as that written by Alphonse de Lamartine, in addition to literature by Balzac and George Sand. As a sign to what’s to come, the story mentions a 1788 well-known romantic book by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, a tragic love story that ends with the heroine’s death:

She had read Paul et Virginie and dreamed of the bamboo hut, Domingo the nigger, Faithful the dog, and especially of the sweet friendship of a dear little brother who goes to fetch red fruit for you from great trees taller than steeples, or runs barefoot along the sand to bring you a bird’s next. 3Ibid.

Possibly the most harmful, as the author tells his readers, were the “trashy” novels which planted sentimental ideas in her head. These novels were smuggled by a cleaning lady into the convent and handed to the teenage girls:

There was an old maid who used to come to the convent every month, for a week, to mend the linen. […] She would tell stories, bring you the news, do your errands in town, and lend the big girls, clandestinely, one of the novels she always kept in the pocket of her apron, from which the good lady herself devoured long chapters, in the intervals of her task. They were about love, lovers, loving, martyred maidens swooning in secluded lodges, postilions slain every other mile, horses ridden to death on every page, dark forests, aching hearts, promising, sobbing, kissing and tears, little boats by moonlight, nightingales in the grove, gentlemen brave as lions, tender as lambs, virtuous as a dream, always well dressed, and weeping pints. For six months, at the age of fifteen, Emma dabbled in the remains of old lending libraries. 4Ibid, 34.

Emma also had a great interest in the novels of Walter Scott, the great Scottish writer, famous for classics like Ivanhoe.

From Walter Scott, subsequently, she conceived a passion for things historical, dreamed about coffers, guard-rooms and minstrels. She would have liked to live in some old manor-house, like those chatelaines in their long corsages, under their trefoiled Gothic arches, spending their days, elbows on the parapet and chin in hand, looking out far across the fields for the white-plumed rider galloping towards her on his black horse. 5Ibid, 35.

Madame Bovary was a fan of Walter Scott who was an influential figure in the Romantic movement. Remember, Romanticism (capital R) was not just about love, but all matters related to human passions and emotions, and an appreciation for the natural world. The novel, Madame Bovary, with its tragic details about a small-town unfaithful wife is considered among the first “realist” novels. When this novel was released, Romanticism as a movement in literature, art and music was dying out, and about to be overtaken by Realism. Some of the best known authors of Realist literature, besides Flaubert, are Honoré de Balzac, Émile Zola and Henry James. Thus, it’s not a coincidence that when Flaubert is critical of books being read by teenage Madame Bovary, they are of the Romantic kind eschewed and mocked by the Realists.

She continues to read fiction after she gets married to Charles Bovary. She meets a mysterious man who enchants her at a party she attends with her husband. He’s referred to as the Viscount. She develops a brief obsession about him and fantasizes about being his mistress. His image is woven in her head with an elaborate daydreams:

Even at the table, she had her book with her, and she would be turning the pages, while Charles was eating and talking to her. The memory of the Viscount haunted her reading. Between him and the fictional characters, she would forge connections. But gradually the circle of which he was the centre widened around him, and the halo that he wore, as it floated free of him, spread its radiance ever further, illuminating other dreams. 6Ibid, 54.

Her passion for books and lack of attention to her home, little daughter and husband does not go unnoticed by her mother-in-law. She warns her son against her reading habits:

Busy reading novels, wicked books, things written against religion where priests are made a mockery with speeches taken from Voltaire. It all leads to no good, my poor boy, and anyone with no religion always comes to a bad end.

….

Therefore, it was decided to prevent Emma from reading novels. This was by no means an easy matter. The old lady took it upon herself: on her way through Rouen she was to call in person at the lending library and notify them that Emma was cancelling her subscription. Would they not have the right to tell the police, if the librarian still persisted in his poisonous trade? 7Ibid, 117.

Since most women did not even have the right to work, the act of taking away privileges like membership in a library does not seem surprising. Also, books were expensive, which meant that another family member, that is the breadwinner, might have a final say on what or which books to purchase. Note that just because the mother-in-law is a woman does not mean that she would be understanding of Madame Bovary’s desire to learn or enjoy some “downtime” as a break from the house chores.

After she consummates her first extra-marital affair, her excitement is framed by her literary fantasies:

But, when she looked in the mirror, she was startled by her own face. Never had she had eyes so large, so black, so mysterious. Something subtle, transfiguring, was surging through her. She kept saying to herself: ‘I have a lover! A lover!’, savouring this idea just as if a second puberty had come upon her. At last, she was to know the pleasures of love, that fever of happiness which she had despaired of. She was entering something marvelous where everything would be passion, ecstasy, delirium.

…

She summoned the heroines from the books she had read, and the lyric host of these unchaste women began their chorus in her memory, sister-voices, enticing her. She merged into her own imaginings, playing a real part, realizing the long dream of her youth, seeing herself as one of the great lovers she had so long envied. 8Ibid, 151.

When her first lover abandons her, she becomes severely depressed. Suicide even crosses her mind. She’s in bed for several weeks, too frail and depressed to leave her bedroom. The local priest visits her and watches her dive into a kind of repentant and extreme spirituality:

The priest marvelled at these propensities, even though Emma’s religion could, he recognized, in its fervour, end up close to heresy and even extravagance. But, not being very well versed in these matters, beyond a certain point, he wrote to Monsieur Boulard, bookseller to the archbishop, asking for something decent for one of the fair sex with a good head on her shoulders. The bookseller, as indifferently as if he were shipping kitchen hardware to negroes, threw together a parcel of everything recent in the way of pious literature. There were little question-and-answer manuals, dogmatic pamphlets in the style of de Maistre [Joseph de Maistre was a French writer who was religious, counter-enlightenment and counter revolutionary, and also among the founders of European conservatism], and various novels in pink bindings and a sugary style, churned out by troubadour seminarists or penitent bluestockings. There was Pensez-y bien; l’Homme du monde aux pieds de Marie, par M. de—, décoré de plusieurs ordres [Think of This; The Man of the World at the Feet of Mary by the distinguished Monsieur de—]; des Erreurs de Voltaire, à l’usage des jeunes gens [On the Errors of Voltaire, for the use of Young People], etc.

Madame Bovary was not yet clear-headed enough to be applying herself seriously to anything; indeed, she went at this reading in too great a hurry. […] she thought herself seized with the finest Catholic melancholy that ever an ethereal soul could convceive of. 9Ibid, 198-199.

Her secret affair is not known to others but those around her, family, acquaintances and clergy, are aware of her “failure” in her role as a mother and wife. The choice of books is an implicit condemnation, a purification of her mind from the books she is used to reading since her youth. The book on the errors of Voltaire for young people, for example, is a clear attempt to bring back an intellectually lost person.

Also, it should be noted, that the priest was uncomfortable with her sudden religious fervor. One of two reasons could explains this. Traditionally men did not always find it appropriate for women to display uncontrollable, intense emotions, even in the context of spirituality. Another reason is the priest’s realization, as it was a common belief at the time, that women are too emotional, perhaps hysterical, and could rapidly, with the aid of books, swing between extremes. So her sudden religiosity was, in his eyes, a feminine condition, not grounded in firm faith.

Later, with her second affair, her excitement is revived. Again, the author draws a line between her adulterous actions under the sheets of bed and the romantic ideas on the sheets of paper of books she’s passionate about.

For fear of being seen, she did not ordinarily go by the quickest way. She scurried along dismal alley-ways, and she emerged in a sweat towards the far end of the Rue Nationale, near the fountain that stands there. This is the place for theatres, taverns and whores.

…

She was the lover in every novel, the heroine in every play, the vague she in every volume of poetry. 10Ibid, 246-247.

Unanswered questions:

Gustave Flaubert could be praised for his sympathetic portrayal of a woman living in a patriarchal society where her happiness and satisfaction in life did not matter much to those around her. However, the fact that the author killed his heroine sparks a debate about which side he belonged to. The same applies to how he viewed the increasingly popular pastime of reading novels for women. He left behind some unanswered questions:

1. Did Flaubert intend to lay the ultimate blame of Madame Bovary’s moral corruption on “sentimental novels”?

2. Did books plant bad ideas into her head or did Madame Bovary already have a corrupt character and fiction was merely the spark?

3. Did Flaubert believe, like many people in the 19th century, that women were particularly vulnerable to the silly, romantic fantasies of fiction?

4. If novels corrupted Madame Bovary, was her mother-in-law, in Flaubert’s eyes, justified in curbing her freedoms of reading?

Regardless of his honest portrayal of an unhappy wife, Flaubert most likely subscribed to the same negative views of his time about women, and particularly about them reading fiction. If he were to come back today, he would probably bemoan, as an author, the continual decline in reading, but one wonders how his views would change considering that women today are more likely to read fiction than men?

You might also like:

Madame Bovary: The scandalous scenes

Why Gustave Flaubert was put on trial for Madame Bovary?

BOOK: MADAME BOVARY

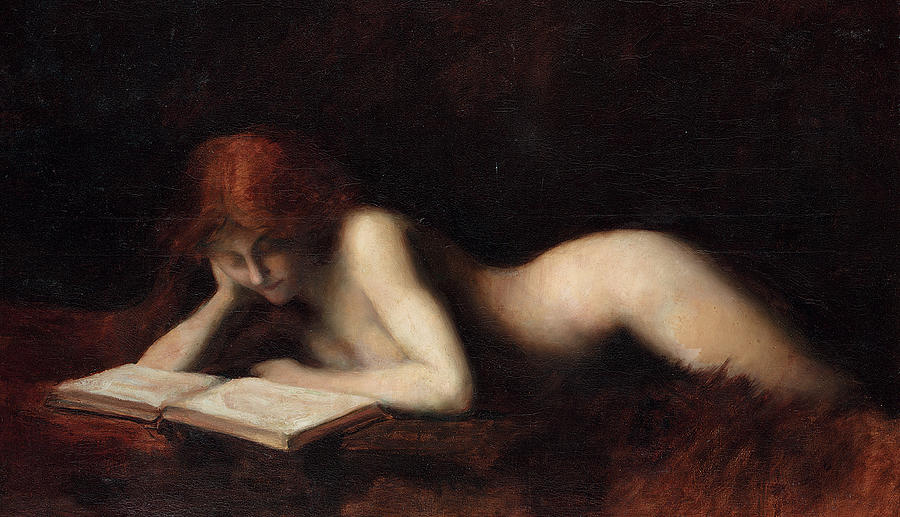

Through art: Sexist views of women who read from yesteryear

What art can tell us about the social anxiety towards women who read

BOOK: MADAME BOVARY

Endnotes