Who was the FLQ?

In the early 1960s, a separatist movement in the Canadian province of Quebec emerged. It was a product of centuries of marginalization of French heritage and language by the Anglo-Canadian majority. Among the groups that appeared was one that was both communist and militant: FLQ (French acronym for Liberation Front of Quebec). FLQ militants planted bombs and carried out kidnappings. They expected the population to rise up in arms following their actions. Their violence reached a boiling point, in what became known as the October Crisis, when they kidnapped two men: a British diplomat, James Cross, and the number 2 man in Quebec, Pierre Laporte, the Deputy Premier. Canadian Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, enforced the emergency laws of War Measures Act, for the only time in Canadian history during peacetime. More than 450 people were arrested without warrants and thrown behind bars. The decision was supported by the Permier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa. Pierre Laporte was killed but James Cross survived.

In exchange for handing over James Cross, the kidnappers were given asylum in Cuba. By 1982, they all returned to Canada. During the crisis, the public across Canada, including Quebec, were in support of the use of force against the militants. After the October Crisis almost all independist movements declared that only peaceful methods should be employed to achieve their goal, rather than a path of violence and terror.

Why the FLQ released this manifesto?

The publication of the 1970 manifesto, at the center of the October Crisis, was one of seven demands by FLQ kidnappers in order to release James Cross. Radio-Canada without official government permission, nor opposition, read it in its original French. The publication created a great controversy. Many opponents were shocked that the government would release a text written by militants. In hindsight, it was probably the right decision since it was already in the hands of the public. Additionally, its intended harmful effect never actually took place.

The failed manifesto

The FLQ militants wrote this manifesto expecting upon publication a mass protest or a general strike. William Tetley, McGill University professor, documented the outcome in his book on the October crisis: “There was no labour uprising or strike, let alone a general strike. Students held meetings in their colleges and universities [to discuss it], but there were no demonstrations or marches in the streets, no riotous confrontations with police, no breaking of windows, no looting, no property damage, and no personal injury or arrests.” 1William Tetley, The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider’s View, (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 36.

The boring manifesto

The manifesto was written in a provocative language, full of epithets, intended to incite a violent uprising. However, it had almost no effect. It was too long and too vague on what to do next. “Make your revolution yourselves in your neighbourhoods” (close to the end of the text) is not a strategy that supporters could follow. It seemed more like a rant mixed with a utopian vision about the future. The general public was either turned off by the violence of the FLQ or saw them as they really were, a bunch of naive yet violent activists.

A note on the language

One of the most sensitive issues in French Canada until today is the protection of their language. Many French-Canadians are on the look-out for contamination of English words and expressions, especially in the media. However, reality on the street is different. It is very common to see Montrealers, for example, speaking “franglais.” Despite this being an important cause for “nationalist” and separatist Quebecers, the FLQ did not pay it much attention. Well, they aimed higher than protection of language and culture. In their use of “franglais” in the manifesto , they were also speaking like members of the Quebec working class. And by doing so, they could avoid sounding like the bourgeoisie and the intellectuals of their own society, whom they despised. Note the use of English words like “big-boss” and “cheap labor” in the second paragraph of the manifesto in the original French.

The entire text (with important passages highlighted in blue):

The people in the Front de Liberation du Québec are neither Messiahs nor modern-day Robin Hoods. They are a group of Quebec workers who have decided to do everything they can to assure that the people of Quebec take their destiny into their own hands, once and for all.2Dimitry Anastakis, Death in the Peaceable Kingdom: Canadian History since 1867 through Murder, Execution, Assassination, and Suicide, (University of Toronto Press, 2015), 219-220.

The Front de Libération du Québec wants total independence for Quebeckers; it wants to see them united in a free society, a society purged for good of its gang of rapacious sharks, the big bosses who dish out patronage and their henchmen, who have turned Quebec into a private preserve of cheap labour and unscrupulous exploitation .The Front de Libération du Québec is not an aggressive movement, but a response to the aggression organized by high finance through its puppets, the federal and provincial governments (the Brinks farce (1), Bill 69 (2), the electoral map (3), the so-called “social progress” (4) tax, the Power Corporation, medical insurance — for the doctors, (5) the guys at Lapalme (6)…)

1. Using the uncertainty created by the rise of the separatist movement as a pretext, the company Royal Trust organized, two days before the Quebec election of April 29, 1970, the transfer from Montreal to Toronto of a boxes of securities in eight truckloads of Brinks. The event which appeared in the front pages of papers the following day, was heavily exploited by the National Union of Jean-Jacques Bertrand, the Liberal followers of Robert Bourassa and those behind Pierre Trudeau against the Parti Québécois of René Lévesque. The “Brinks coup” became a symbol of figures of economic intimidation, opposing the independence of Quebec.

2. Bill 63 was presented to the National Assembly in October 1969 by Unionist Prime Minister Jean-Jacques Bertrand. Because it grants parents the free choice of the language of instruction for their children, this bill was denounced as in favor of the anglicization of immigrants. The Front of French Quebec (a dissident party of worker and student unions) organized demonstrations in major cities of Quebec. On October 31, 1969, 40,000 demonstrators and 1,000 police officers met in front of the National Assembly: the confrontation left 40 wounded. Following another demonstration held in Montreal in November, the Municipal Council prohibited public meetings. Bill 63 was passed soon after. Bombs planted by the FLQ during this period damaged the campuses of Loyola and McGill universities.

3. The electoral map (that is to say the division of the territory into constituencies) presented flagrant irregularities. Despite a reform in 1965, certain rural ridings in Quebec still had three or four times less voters than others in urban areas, which allowed the National Union to take power in 1966 with 150,000 fewer votes than the Liberal Party. In the 1970 elections, the Union Nationale and the Rassemblement Creditiste collectively obtained as many votes as the Parti Quebecois, but had a total of 29 deputies elected against 7.

4. The so-called “social progress” tax was levied by the federal government from January 1969 onwards to finance a new health insurance plan established without the agreement of the provinces. During that year, Quebec resisted federal intervention, $110 million was collected from Quebec taxpayers without them being able to benefit from the plan. Ottawa refused to reimburse.

5. In 1970, the health insurance plan was extended to the entire population of Quebec. At the same time, the government was forced to accept the principle of payment for physicians on a fee-for-service basis, which seemed to guarantee them unlimited salary treatment.

6. On April 1, 1970, the Federal Post Office Department, under the approval of Pierre Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, cancelled their contract for the transport of mail by subcontracting it to small private companies. The “Lapalme boys” were the 450 truckers who lost their jobs in that process. They launched for five months more than 800 attacks on the postal installations; 42 protesters were injured. They became a symbol of left resistance in Quebec. One of the demands of FLQ was their rehiring. In its repeated bombing of mail boxes and post offices (24 bombs in eight years), the FLQ violently showed its support for these workers’ struggle and their rejection of federalism. The mailbox was an unusual symbol but an easy target. Also, the re-reinstatement of the “guys from Lapalme” was one of the conditions set by the FLQ for the release of the hostage James Richard Cross in October 1970. It would never take place.

The Front de Libération du Québec finances itself — through voluntary (sic) taxes levied on the enterprises that exploit the workers (banks, finance companies, etc….) (7).

7. A satiric allusion to a lottery instituted in 1968 by mayor Jean Drapeau, called “voluntary tax” in order to circumvent the prohibition of the criminal code, and intended to fulfil the immense debt incurred by the Montreal metro and the Universal Exhibition (more than three times the original budget). From 1969 to 1970, the FLQ “collected” more than $250,000 from various banks, stole three or four thousand sticks of dynamite from construction sites and stole military equipment worth nearly $60,000. In 1969, the Chénier cell also developed an effective fraud system targetting American Express.

“The money powers of the status quo, the majority of the traditional tutors of our people, have obtained from the voters the reaction they hoped for, a step backwards rather than the changes we have worked for as never before, the changes we will continue to work for.” (René Lévesque, April 29, 1970) (8).

8. A quote from a speech given at the Paul-Sauvé center in Montreal, the evening of the Liberal victory in the general elections. Coming second with 24% of the vote, the PQ (Parti Québecois) only collected 6% of the seats, because of the electoral map and the majority voting system. The electoral campaign was thus treated as a fraud. The writer Jacques Ferron remarked about the rise of the term “felquiste,” (a reference to FLQ) noting that it rhymes with “péquiste” (for PQ).

Once, we believed it worthwhile to channel our energy and our impatience, in the apt words of René Lévesque, into the Parti Québécois, but the Liberal victory shows that what is called democracy in Quebec has always been, and still is, nothing but the “democracy” of the rich. In this sense the victory of the Liberal party is in fact nothing but the victory of the Simard-Cotroni (9) election- fixers. Consequently, we wash our hands of the British parliamentary system; the Front de Libération du Québec will never let itself be distracted by the electoral crumbs that the Anglo-Saxon capitalists toss into the Quebec barnyard every four years. Many Quebeckers have realized the truth and are ready to take action. In the coming year Bourassa is going to get what’s coming to him: 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized! (10)

9. At the head of a gigantic industrial complex based in Sorel, the Simard clan had benefited since the 1940s from the favoritism of the two levels of government, notably for obtaining contracts for armament and shipbuilding. One of the Simard daughters married Robert Bourassa in 1958. From 1970 to 1976, Claude Simard sat on the Council of Ministers chaired by Bourassa, his brother-in-law. An FLQ bomb exploded near the Simard buildings in Tracy in June 1970.

Vincenzo Cotroni was the godfather of the first mafia established in Canada. Their underworld activities apparently included the funding of political parties: an offer of contribution made by one of Cotroni’s men to the future minister Pierre Laporte, shortly before the 1970 elections, is noted here.

10. Mocking allusion to the 100,000 jobs promised by Robert Bourassa, young leader of the Liberal Party, during the election campaign of 1970, The unemployment rate in Quebec then bordered on 10%.

Yes, there are reasons for the Liberal victory. Yes, there are reasons for poverty, unemployment, slums, for the fact that you, Mr. Bergeron of Visitation Street, and you too, Mr. Legendre of Ville de Laval, who make F10,000 a year, do not feel free in our country, Quebec.

Yes, there are reasons, the guys who work for Lord know them,(11) and so do the fishermen of the Gash, the workers on the North Shore; the miners who work for Iron Ore, for Québec Cartier Mining, for Noranda know these reasons too. (12) The honest workingmen at Cabano, the guys they tried to screw still one more time, they know lots of reasons.(13)

11. The Lord Company metallurgical workers walked out in August 1968 in order to obtain union recognition. Three FLQ bombs were planted in solidarity with them the following fall.

12. Between 1965 and 1970, the Quebec mining industry experienced around thirty work stoppages involving several thousand workers. Noranda Mines’ head office in Montreal was badly damaged by the explosion of a Felquist bomb in January 1969. (See also note 17.)

13. During the summer of 1970, the citizens of the small forest town of Cabano, in the hinterland of Rivière-du-Loup, took up arms and neutralized the provincial police. They demanded the construction of a wood processing plant that had been promised to them, which they never got, despite a disastrous unemployment rate.

Yes, there are reasons why you, Mr. Tremblay of Panet Street and you, Mr. Cloutier who work in construction in St. Jérôme, can’t afford “Golden Vessels” with all the jazzy music and the sharp decor, like Drapeau the aristocrat,(14) the guy who was so concerned about slums that he had coloured billboards stuck up in front of them so that the rich tourists couldn’t see us in our misery.(15)

14. Named after the poem by Émile Nelligan, Le Vaisseau d’or is a concept restaurant-concert invented by the mayor Jean Drapeau, who owned and managed it according to an elite vision of culture to say the least. The chic Vaisseau d’or was sacked during a police strike (see note 23) and sank definitively in January 1971, fourteen months after its opening.

15. The blue and white panels were seven feet high and were part of the City of Montreal’s preparations for the 1967 World Exposition. The FLQ copiously sprayed them with graffiti, occasionally calling the public to “visit the slums!”

Yes, Madame Lemay of St. Hyacinthe, there are — reasons why you can’t afford a little junket to Florida like the rotten judges and members of Parliament who travel on our money. The good workers at Vickers and at Davie Shipbuilding, the ones who were given no reason for being thrown out, know these reasons; so do the guys at Murdochville that were smashed only because they wanted to form a union, and whom the rotten judges forced to pay over two million dollars because they had wanted to exercise this elementary right.(16) The guys of Murdochville are familiar with this justice; they know lots of reasons. (17)

16. Some strikes occurred in the major shipyards of Canadian Vickers (Montreal) and Davie Shipbuilding (Lauzon), shortly before these companies permanently shut down in the late 1960s.

17. The Copper-Noranda miners’ strike in Murdochville (March October 1957) had devolved into a violent confrontation between the strikers and the provincial police and private guards. Quebec had proclaimed the Law of the Riot after installations of the company had been blown up. The miners obtained union recognition eight years later, but in 1970 the Supreme Court of Canada ordered them to pay the company $2.5 million in damages.

Yes, there are reasons why you, Mr. Lachance of St. Marguerite Street, go drowning your despair, your bitterness, and your rage in Molson’s horse piss. And you, the Lachance boy, with your marijuana cigarettes…

Yes, there are reasons why you, the welfare cases, are kept from generation to generation on public assistance. There are lots of reasons, the workers for Domtar at Windsor and East Angus know them;(18) the workers for Squibb and Ayers,(19) for the Quebec Liquor Commission(20) and for Seven-up(21) and for Victoria Precision,(22) and the blue collar workers of Laval and of Montreal and the guys at Lapalme know lots of reasons.

18. Domtar Pulp Paper employees periodically walked out to demand better pay. It was in the fall of 1968 that they began their longest strike, during which they occupied the factories of Windsor and East Angus and took up arms to resist the provincial police and the private guards of the company. Domtar was the target of three bombs dropped by the FLQ between 1968 and 1970.

19. Owned by the Ayers de Lachute family, who owned most of the local businesses (including the City Council), Dominion Ayers employed several hundred workers in its textile and plywood factories. A third of employees (paid at an average rate of $ 1an hour) had lost at least one finger at work, many suffer from skin and lung diseases. A four-month strike in the fall of 1966 culminated in the intervention of the company’s private security officers. An FLQ bomb exploded at the Ayers factory around the same time.

20. The 5000 employees of administration walked out for two and a half months from Christmas 1964 (“Are you thirsty? We are hungry!”) And another five months from the summer of 1968. Five bombs exploded, out of six, near the branches of the Régie des alcools in the fall. They were planted by the FLQ.

21. The long strike at the Seven-Up bottling plant (June 1967-July 1968) was marked by the violence of the police forces responsible for protecting the strikebreakers and suppressing a large demonstration of support which, in February 1968, wounded dozens. An FLQ bomb exploded at the factory director’s residence, and another in the factory itself in Ville Mont-Royal.

22. The metallurgical workers at Victoria Precision in Montreal stopped the machines at the beginning of 1968 in order to obtain union recognition. They were dismissed after several months of strike. An FLQ bomb exploded at the factory in late summer.

The workers at Dupont of Canada know some reasons too, even if they will soon be able to express them only in English (thus assimilated, they will swell the number of New Quebeckers, the immigrants who are the darlings of Bill 69).

These reasons ought to have been understood by the policemen of Montreal, the system’s muscle; they ought to have realized that we live in a terrorized society, because without their force and their violence, everything fell apart on October 7. (23)

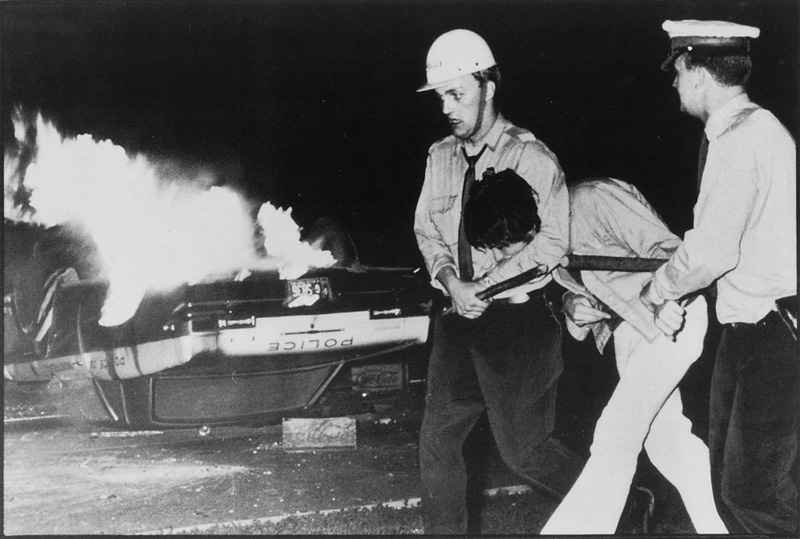

23. On October 7, 1969, the 3,700 police officers from Montreal went on strike. The Canadian army was in charge of the metropolis for the first time since the strike of the trams of 1944. Before the police officers submitted to the special law adopted by the provincial government (return to work at midnight under penalty of imprisonment and fine), Montreal was the scene of several rampages and a murderous shooting at the Murray Hill garage (see note 24). Returning to work with the promise of salary increases, the police soon made, with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, hundreds of “preventive” arrests of community and union organizations that formed the heart of the municipal opposition.

We’ve had enough of a Canadian federalism which penalizes the dairy farmers of Quebec to satisfy the requirements of the Anglo-Saxons of the Commonwealth; which keeps the honest taxi drivers of Montreal in a state of semi-slavery by shamefully protecting the exclusive monopoly of the nauseating Murray Hill,(24) and its owner — the murderer Charles Hershorn and his son Paul who, the night of October 7, repeatedly tore a .22 rifle out of the hands of his employees to fire on the taxi drivers and thereby mortally wounded Corporal Dumas, killed as a demonstrator.(25) Canadian federalism pursues a reckless import policy, thereby throwing out of work the people who earn low wages in the textile and shoe industries, the most downtrodden people in Quebec, and all to line the pockets of a handful of filthy “money-makers” in Cadillacs.(26) We are fed up with a federalism which classes the Quebec nation among the ethnic minorities of Canada.(27)

24. The monopoly granted to the Murray Hill bus company for passenger transportation between Dorval airport and Montreal has long raised the anger of taxi drivers. Founded in September 1968 by Germain Archambault, the Taxi Liberation Movement, succeeded a month later in blocking the airport and the city center of the metropolis. Private company guards were planted on the roofs and opened fire on the rebellious crowd and left one dead and dozens injured. Bombs planted by the FLQ had exploded the previous fall at the Murray Hill garage and at its owner’s residence in Westmount.

25. Here, the authors of the Manifesto seem to ignore the fact that Corporal Robert Dumas was embedded among the demonstrators on behalf of the provincial police.

26. In 1970, the median annual wages of textile workers was $5,225 for men and $3,270 for women. Dominion Textile, for example, had workshops in most major cities in Quebec and has experienced two monster strikes per decade since the 1930s. Two factories in this company were hit by FLQ bombs in the summer of 1966.

27. The report of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (Laurendeau-Dunton) reveals in 1965 that the average income of French Canadians, even the bilingual ones, ranks them 12th out of the 14 main ethnic groups in the country. Canada, just ahead of the Italians and the Amerindians.

We, and more and more Quebeckers too, have had it with a government of pussy-footers who perform a hundred and one tricks to charm the American millionaires, begging them to come and invest in Quebec, the Beautiful Province where thousands of square miles of forests full of game and of lakes full of fish are the exclusive property of these all-powerful lords of the twentieth century. We are sick of a government in the hands of a hypocrite like Bourassa who depends on Brinks armoured trucks, an authentic symbol of the foreign occupation of Quebec, to keep the poor Quebec “natives” fearful of that poverty and unemployment to which we are so accustomed.

We are fed up with the taxes we pay that Ottawa’s agent in Quebec would give to the English-speaking bosses as an “incentive” for them to speak French, to negotiate in French. Repeat after me: “Cheap labour is main d’oeuvre à bon marché in French.” (28)

28. Law 63 (see note 2) entrusted the Office de la lange française with the task of spreading the use of French in private enterprises, which resulted in a significant increase in the Office’s staff in Montreal.

We have had enough of promises of work and of prosperity, when in fact we will always be the diligent servants and bootlickers of the big shots, as long as there is a Westmount, a Town of Mount Royal, a Hampstead, an Outremont, all these veritable fortresses of the high finance of St. James Street and Wall Street; we will be slaves until Quebeckers, all of us, have used every means, including dynamite and guns, to drive out these big bosses of the economy and of politics, who will stoop to any action however base, the better to screw us.

We live in a society of terrorized slaves, terrorized by the big bosses, Steinberg, Clark, Bronfman, Smith, Neopole, Timmins, Geoffrion, J.L. Lévesque, Hershorn, Thompson, Nesbitt, Desmarais, Kierans(29) (next to these, Rémi Popol the Nightstick, Drapeau the Dog, the Simards’ Simple Simon and Trudeau the Pansy are peanuts!). (30)29. Metnioning the last names of Samuel Steinberg, Samuel and Charles Bronfman as well as Paul Desmarais was enough for the audience of the manifesto to recognize them. The list mentions also Charles Bertram Neapole, former VP the Royal Bank, president of the Montreal Stock Exchange from 1966; the Timmins family, major shareholder of the mining companies Noranda and Hollinger; Geoffrion and Lévesque, major securities brokers; Charles Hershorn, owner of Murray Hill buses; Deane Nesbitt, securities broker; and Éric William Kierans, president of the Montreal Stock Exchange from 1960 to 1963, Liberal minister in Quebec, defeated candidate for PLQ leadership in 1968, then Liberal minister in Ottawa.

30. Spokesman for the right wing of the National Union, Me Rémi Paul, Minister of Justice until May 1970, was one of those who were most fond of flamboyant statements (“there are 3000 terrorists in Quebec”) and questionable connections (“René Lévesque is the Fidel Casto of Quebec”).

For his part, the mayor of Montreal saw his private house and his town hall damaged by the FLQ bombs in 1968 and 1969. The Hôtel Victoria, residence of Prime Minister Bourassa in Quebec, barely avoided the same fate in 1970 – the bomb was defused (see note 9.)

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was 51 years old in 1970, and the Ottawa Citizen used his prolonged celibacy as the pretext for launching rumors against his sexual orientation.

31. The work of the architect Pier Luigi Nervi, the building of the Montreal Stock Exchange is built with Italian capital, including that provided by the Spiritu Sanctu Bank of Rome.

32. Respectively, the rector of the Université de Montréal, the rector of UQAM and the vice-rector of McGill University.

There are more and more of us who know and suffer under this terrorist society, and the day is coming when all the Westmounts of Quebec will disappear from the map.

Workers in industry, in mines and in the forests! Workers in the service industries, teachers, students and unemployed! Take what belongs to you, your jobs, your determination and your freedom. And you, the workers at General Electric, you make your factories run; you are the only ones able to produce; without you, General Electric is nothing!

Workers of Quebec, begin from this day forward to take back what is yours; take yourselves what belongs to you. Only you know your factories, your machines, your hotels, your universities, your unions; do not wait for some organization to produce a miracle . Make your revolution yourselves in your neighbourhoods, in your places of work. If you don’t do it yourselves, other usurpers, technocrats or someone else, will replace the handful of cigar-smokers we know today and everything will have to be done all over again. Only you are capable of building a free society.We must struggle not individually but together, till victory is obtained, with every means at our disposal, like the Patriots of 1897-1898 (those whom Our Holy Mother Church hastened to excommunicate, the better to sell out to British interests).

In the four corners of Quebec, may those who have been disdainfully called lousy Frenchmen(33) and alcoholics begin a vigorous battle against those who have muzzled liberty and justice; may they put out of commission all the professional holdup artists and swindlers: bankers, businessmen, judges and corrupt political wheeler-dealers. …

33. Allusion to a comment by Pierre Trudeau (then the Minister of Justice) on the subject of speaking “Quebecker French.” An insult made worse by the fact that it was made in English on the airwaves of an Ontario television.

34. The release of 23 “political prisoners,” sympathizers and detained FLQ activists, were part of the conditions laid down by the Liberation cell for the release of the diplomat James Richard Cross.

Note: The above text is available in the original language (French) on this page.

You might also like:

White Niggers of America: A call to arms by a Quebec terrorist

Summary of the book by Pierre Vallières, one of the leaders of Front de libération du Québec. Read the controversial quotes

BOOK: WHITE NIGGERS OF AMERICA

How Karl Marx inspired a French-Canadian terrorist

Seven communist ideas in White Niggers of America (1968) could be traced to the writings of Karl Marx

BOOK: WHITE NIGGERS OF AMERICA

Endnotes